10 extraordinary Native American cultural sites protected on public lands

Canyons of the Ancients National Monument, Colorado

Mason Cummings, The Wilderness Society

In honor of Native American Heritage Month this November, we take a look at a few noteworthy Native American cultural sites on public lands.

Native American Heritage Month offers all Americans the opportunity to recognize and honor tribes who understood the value of wilderness long before European Americans ever laid eyes on bison or redwoods—or, indeed, decided to call certain places “wilderness.”

A number of the national monuments, parks and other sites we cherish contain major historical and cultural resources connected to these tribes. In many cases, the land that surrounds them might not have remained in good condition without the Antiquities Act, a law passed in 1906 that allowed presidents to protect natural and cultural sites as national monuments. The Antiquities Act was first signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt and has been used on a bipartisan basis by 16 presidents since then (including President Barack Obama). It is likely that some of these special places would have been obscured by development—or demolished entirely—without this law and the strong movement to preserve public lands that it exemplifies.

Right now, treasured landscapes like Utah's Bears Ears and Nevada's Gold Butte are in desperate need of similar attention. Home to countless important Native American archaeological and cultural sites, they have recently fallen prey to vandalism, reckless off-road vehicle use and other destructive behavior.

In November, let's take a look at some places that preserve traces of Native American culture that are hundreds (or even thousands) of years old, and think of the spots that still need to be protected.

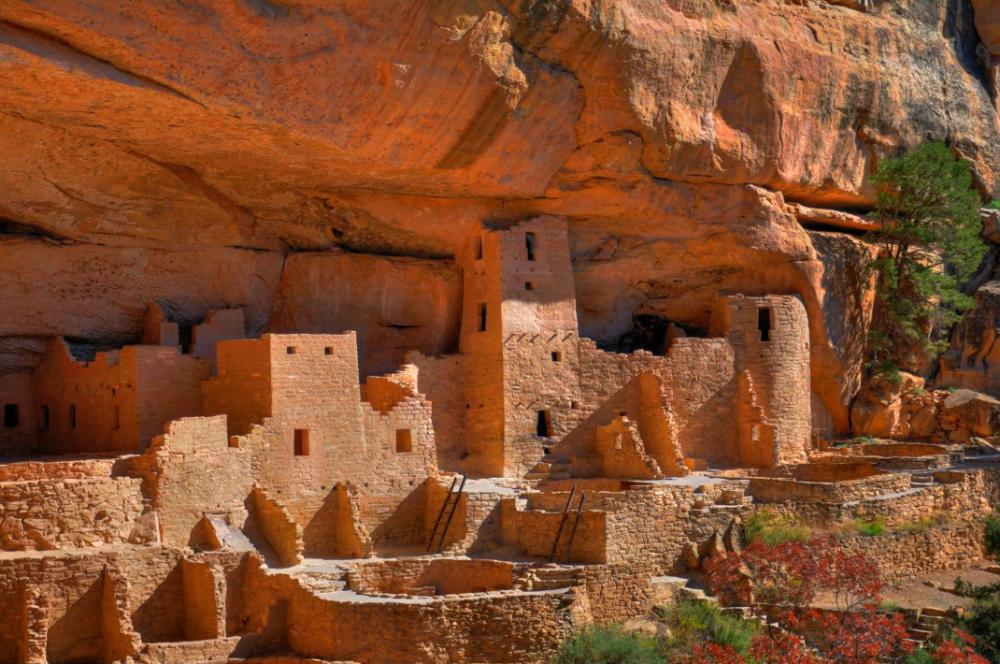

Mesa Verde National Park (Colorado)

Mesa Verde was the first national park designated with the express purpose of preserving "the works of man"—in this case the remnants of 6th-12th century Ancestral Puebloans, as exemplified by more than 4,000 known archeological sites, including some of the most notable and well-preserved in the U.S. The park’s signature attractions are some 600 ancient dwellings carved into rock alcoves, stumbled upon by a pair of cowboys—who called it “Cliff Palace”—in the late 19th century. At that point, Mesa Verde had been vacant for hundreds of years. Experts think the last Puebloan residents of the area were forced out when a booming population eventually exhausted natural resources and was torn apart by internal strife. Since 1906, the park has been preserved for the enjoyment and education of all Americans (though oil and gas development in the area pose a threat to the landscape). Tours of the site offer details on these lives, and trails provide opportunities for hiking and snowshoeing. The 360-degree panoramic view at Park Point is one of the most breathtaking in the country.

Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado

Steve Dunleavy, Flickr

Casa Grande Ruins National Monument (Arizona)

The 14th century “great house” around which this monument is centered was once part of a chain of settlements along the Gila River and is considered one of the largest prehistoric structures ever built in North America. Prized as a trace of ancient Sonoran Desert dwellers who developed wide-scale irrigation farming and a large trade network before leaving the area around the year 1450, the Casa Grande was originally protected as our country’s first archaeological reserve, in 1892. The building, whose exact purpose remains unknown, gained national monument status from President Woodrow Wilson in 1918. Today, several Native American groups claim an ancestral link to the builders and occupants of the monument’s eponymous structure.

Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, Arizona

National Park Service

Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks National Monument (New Mexico)

The campaign that led a stretch of picturesque land near Las Cruces, New Mexico was a major initiative of The Wilderness Society—but it was led in part by local tribal leaders, a fitting testament to the significance of this place to Native Americans. The Ysleta del Sur Pueblo tribe asked that the area be protected in part to preserve an expanse of ancient petroglyphs, and the Fort Sill Apache tribe, considered modern-day successors to the Apache that originally inhabited parts of the Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks region, requested that they be accepted as partners in managing the monument for future generations. The mountain ranges and rugged plains here contain traces of civilizations hundreds of years old (and in some cases much older); the Paleo-Indian peoples who once roamed the Potrillo grasslands hunted now-extinct game like giant ground sloths thousands of years before Christopher Columbus was born. Stretches of land protected by the monument contain some of the earliest known prehistoric habitation sites in southern New Mexico, among many significant historical and archaeological resources.

Western Arctic, AK

Florian Schulz

Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks National Monument was designated by President Obama under the Antiquities Act.

Effigy Mounds National Monument (Iowa)

The only national monument in Iowa, Effigy Mounds was protected by President Harry Truman in 1949 in order to preserve its namesake series of sacred hillocks, constructed by a culture that inhabited land along the upper Mississippi River, stretching east to Lake Michigan (what is now parts of Iowa, southeast Minnesota, southern Wisconsin and northern Illinois). Numbering more than 200, the mounds were built over thousands of years in a variety of shapes ranging from simple cones to bison and birds. Though the exact function of the mounds as a whole remains unknown, some are burial sites, and experts think that others may have acted as territorial markers. Whatever the mounds’ purpose, more than 15 modern-day tribes, ranging from Minnesota to Oklahoma, are considered to be culturally associated with them. The largest and best-preserved chain of mounds, the evocatively named “Marching Bears,” can only be fully appreciated from overhead.

Effigy Mounds National Monument, Iowa

National Park Service

Chaco Culture National Historical Park (New Mexico)

Unfortunately, oil and gas development currently threatens the beauty and tranquility of this park and adjacent land—and it would be a true shame to lose it. Between 850 and 1250 CE, Chaco Canyon, in what is now northwest New Mexico, was a major center of Ancestral Puebloan culture. Today, the surrounding area is protected to preserve the history of those people, including majestic public and ceremonial buildings that are among America’s most significant intact examples of pre-Columbian culture. These multi-story “Great Houses” were truly monumental undertakings, sometimes involving decades of construction, and many were connected by a system of roads to other buildings in the region. It is thought that this area was once a unique gathering place for different clans to meet—a center for trade and cultural exchange that remains a hallowed landmark today.

In 2013, the park received International Dark Sky designation for being one of the best places in the United States to stargaze (due to its distance from artificial light pollution).

Chaco Canyon National Historical Park, New Mexico

Mason Cummings, The Wilderness Society

Hopewell Culture National Historical Park (Ohio)

This park protects five different archaeological sites containing artifacts of the broadly defined Hopewell culture, chiefly earthworks and ancient mounds. The people who flourished in this area practiced a wide array of spiritual, political and social customs, but are considered to be related due to the elements this park preserves: their similar construction of earthen-walled enclosures and mounds, with the former often appearing as squares, circles and other geometrically precise shapes. A variety of archaeological figures have devoted their careers to finding out more about the Hopewell culture.

Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio

Ton Engberg, National Park Service

Canyons of the Ancients National Monument (Colorado)

This sprawling, landscape-scale monument in southwest Colorado contains thousands of known archaeological sites that have yielded invaluable historical information on Ancestral Puebloan (sometimes referred to as “Anasazi”) and other indigenous cultures. A nearby museum contains millions of items chronicling those peoples as well as historic Ute and Navajo populations (the protected area is considered to have ancestral links to dozens of modern-day tribal nations). Three original villages within the monument have been prepared for visitors and outfitted with interpretive signage, making it an essential destination for anyone with an abiding interest in Native American culture (though a huge number of dwellings, shrines, petroglyphs and other artifacts remain unlabelled).

Canyons of the Ancients National Monument, Colorado

Mason Cummings, The Wilderness Society

Aztec Ruins National Monument (New Mexico)

Aztec Ruins National Monument was protected as a national monument in 1923 and named a World Heritage site in 1987 (as part of Chaco Culture National Historical Park) for its well-preserved examples of Pueblo architecture—the same features that still draw tourists from around the country. So why is it called “Aztec Ruins”? Early white explorers initially mistakenly identified the buildings on-site as traces of the Mexican Aztec culture, rather than the work of (even older) indigenous peoples, and it still bears the original, ill-gotten title. Despite this, the monument is an important place for Ancestral Puebloans, its ancient “great houses” and associated “kivas”—ceremonial chambers—serving testament to the legacy of its old inhabitants.

Artifacts discovered in the ruins have included food remnants, clothing, tools and jewelry, offering a glimpse at the way Ancestral Puebloans used natural resources and traded with other peoples.

Aztec Ruins National Monument, New Mexico

National Park Service

Ocmulgee National Monument (Georgia)

Ocmulgee National Monument contains North America’s only intact “spiral mound,” a 20-foot-tall hillock built by indigenous tribes for purposes that remain unclear. This is just one of the monument’s pieces of major earthwork traced back to South Appalachian Mississippian settlements. The monument, containing seven mounds in all and a collection of more than one million artifacts, was protected along the Ocmulgee River by act of Congress in 1934.

Ocmulgee National Monument, Georgia

denisbin, Flickr

Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument (New Mexico)

Surrounded by the Gila National Forest (and at the edge of the Gila Wilderness), this monument, protected by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1907, is named for its most striking feature—the ruins of interlinked cave dwellings built in five cliff alcoves by the Mogollon peoples who lived in the area in the late 13th- and early 14th century. While the monument covers comparatively little physical ground, it offers a wealth of things for visitors to do once they’ve finished exploring these rare traces of ancient Puebloan culture: activities in the broader area include hiking, bird-watching, camping, fishing and horseback riding.

Ruins in Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, New Mexico

Doc Johnny Bravo, Flickr