A tribute to Howard Zahniser, unsung architect of the Wilderness Act

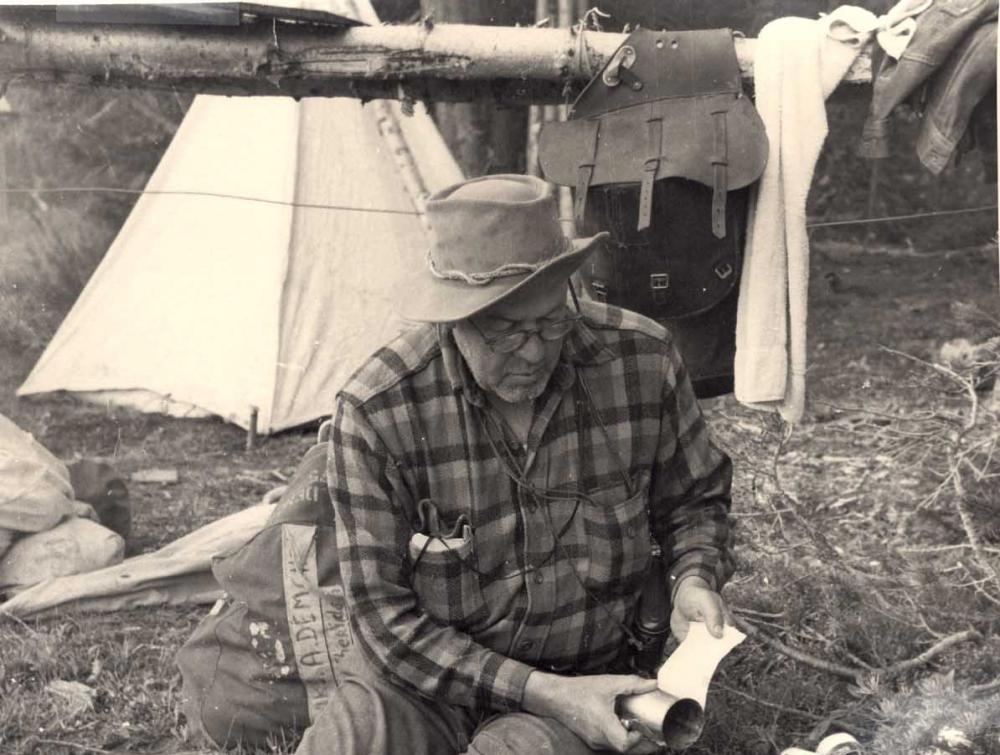

Howard Zahniser

The Wilderness Society

The Wilderness Act, which allows the public to work with Congress to nominate places deserving an especially high level of protection, would not have been possible without a former Wilderness Society leader named Howard Zahniser.

Described as a “career bureaucrat,” the “bookish, polite” Zahniser was not an outsized, iconoclastic figure in the history of American conservation, like hirsute mystic John Muir or two-fisted crusader Theodore Roosevelt. But that professed ordinariness actually underscores the substance of his work in forming our modern idea of wilderness. He was just a dogged man who did the good, hard work of preserving our natural heritage for generations to come.

The son of a Pennsylvania minister, Zahniser displayed a love of the outdoors from a young age, joining the Junior Audubon Club and spending countless hours exploring the Adirondacks throughout his life. After college, he worked for various journalistic outlets before taking a position with the Bureau of Biological Survey (later the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service).

In 1945, his writing experience and wilderness expertise established, Zahniser went to work for The Wilderness Society as executive secretary and editor of its magazine, The Living Wilderness. Over the course of nearly two decades, Zahniser would become a hard-working fixture of the nation’s preeminent public lands advocacy organization, and a major force for change.

The spark for a bold new idea

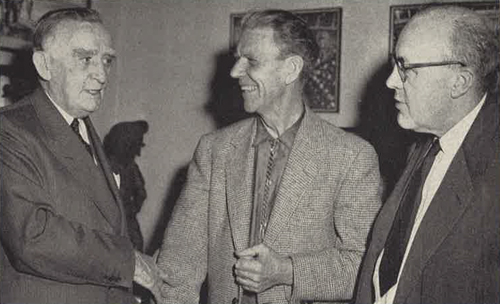

Howard Zahniser (right) confers with Olaus J. Murie (center) and then-Sen. Joseph O'Mahoney, of Wyoming. Photo credit: The Living Wilderness

Formally, the idea for the Wilderness Act is often traced back to an effort led by Zahniser and other conservationists to prevent the Echo Park Dam from being built on the Green River in Dinosaur National Monument in the 1950s. That campaign came to serve as a surrogate for the larger debate over protecting American wildlands, and, with its successful resolution in 1955, Zahniser enjoyed newfound sway among conservation advocates.

It also made Zahniser realize that in the absence of a unified, national framework for protecting the wildest places, conservationists might need to fight such battles endlessly. He conceived of what would become the Wilderness Act partly because he was weary of "a wilderness preservation program made up of a sequence of overlapping emergencies, threats and defense campaigns."

As early as the late-1940s, Zahniser had outlined an idea for how such a law might work, but the Echo Park Dam victory, among other factors, helped lead to the first actual draft, which he completed in May 1956.

Then-Sen. Hubert Humphrey (D-MN) introduced the first version of the wilderness protection bill in 1957, but it didn’t get very far: opposition from industry and rival lawmakers was pointed. This was a portent of the long, arduous process to come.

Eight years in the wilderness

Zahniser’s bill would be rewritten or resubmitted 66 times, subject to 18 public hearings and 16,000 pages of testimony. At some point in the process, Zahniser, allegedly inspired by the seashore near Olympic National Park, added a word he felt perfectly evoked the rugged, unique quality of wilderness-type lands to be spared mankind’s undue abuse, which would become the bill’s quintessential flourish: “untrammeled.”

This word, as opposed to “undisturbed,” would allow for the protection of land that had previously been upset by human activity, but could potentially become whole again if protected as wilderness. More to the point, it bespoke Zahniser’s belief that wilderness designation was intended “not to maintain the status quo but to remove the human trammels that keep natural change from taking place,” as laid out in the 2005 Zahniser biography “Wilderness Forever.”

The process of writing the Wilderness Act wore on Zahniser. "He'd just go and go, often 30 hours at a stretch without sleeping," his wife, Alice, later said. "In the end he just spent himself out."

As a Washington Post article noted, the Wilderness Act “provoked more florid oratory and fiery political debate than any other conservation measure in U.S. history”

As the bill went through revision after revision, Zahniser’s health declined. Chronically ill for many years, he had suffered a heart attack as early as 1951, but was able to continue his work with The Wilderness Society. The process of writing the Wilderness Act was different. "He'd just go and go, often 30 hours at a stretch without sleeping," his wife, Alice, later said. "In the end he just spent himself out."

The language of the bill was chopped into pieces, re-assembled to satisfy a spirit of political compromise. Various substitute bills were introduced that would have undermined the law’s spirit, such as by subjecting wilderness areas to periodic review. As recorded in The Living Wilderness, Zahniser pushed back against obstacles by pointing out that the law was intended to hold our periodic expansionist tendencies at bay: “The nature of our civilization is such as to make wilderness preservation difficult at its best. That is the reason for wilderness legislation.”

Untrammeled and unforgettable

Alice Zahniser (center) receives a pen used to sign the Wilderness Act into law from President Lyndon B. Johnson. Credit: Abbie Rowe via The Living Wilderness

Gradually, support grew for the idea of federally-protected wilderness. The Senate passed a wilderness bill in 1963. But the slog to make the Wilderness Act into law was not yet complete; the legislation awaited action in the House. In remarks delivered to the Fifth Biennial Conference on Wilderness in April 1964, Zahniser expressed hope that a new day was coming:

We are establishing for the first time in the history of the earth a program, a national policy, whereby areas of wilderness can be preserved. That will not be the end of our efforts. That is just the beginning. It is the charter of a program that can endure.

Days later, Zahniser testified for the last time in support of his bill. In May, he passed away, only months after Olaus J. Murie, former president of The Wilderness Society, another fierce advocate for the Wilderness Act.

Zahniser pointed out the law was intended to hold our expansionist tendencies at bay: “The nature of our civilization is such as to make wilderness preservation difficult at its best. That is the reason for wilderness legislation.”

Upon Zahniser’s passing, The Wilderness Society, said in a statement that he was “active to the end in the wilderness preservation efforts that had been so much a part of his life’s work.” A Washington Post editorial presciently noted: “One who knew him well has suggested that the wilderness bill, when it is enacted, will be his monument.”

Indeed it was. The House passed the Wilderness Act in August 1964 nearly unanimously, eight years after Zahniser had polished off his first draft. His elegant definition of the lands it sought to protect remained intact in the bill—one of the few bits to survive from early versions:

A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.

Zahniser’s widow was invited to the bill-signing ceremony in September and received a pen used by President Johnson to make it the law of the land. At last, Americans had a way to permanently protect beloved wild places at the highest possible level.

In the following decades, the system of protected lands established by the Wilderness Act would grow to a total of 111 million acres and become roundly acknowledged as a triumphant achievement of American conservation. Its 50th anniversary has become a cause for celebration and reflection across the country.

A quiet yet indomitable legacy

As a 1984 Washington Post article noted, the Wilderness Act “provoked more florid oratory and fiery political debate than any other conservation measure in U.S. history” to that point (and yet, there “never was a piece of legislation so worthy of the effort”).

Zahniser himself remains relatively obscure. Some have suggested that anonymity, even in the wake of this signature achievement, would have suited the private, modest man. Years later, Alice Zahniser cited one of Howard’s favorite sayings: “you could get anything you wanted done in Congress if you didn't expect to get the credit."

Yet in a September 1994 editorial on Zahniser, The San Francisco Chronicle called on readers to “pay a moment of gratitude today to a little-known American.” Going one step further, it noted that “it is not enough to look back with gratitude. If we value the 30-year legacy of the Wilderness Act, it is even more important to look forward with determination to build on that base and enlarge it.”

Two decades after those words were written, our approach to protecting wild places is growing and evolving, but Zahniser’s importance is undiminished. His place in the annals of American conservation is absolute and unquestioned, his spirit manifest in the limestone ridges of Bob Marshall Wilderness, the old-growth forests of Olympic Wilderness and the myriad mountains, rivers, prairies and swamps protected permanently in hundreds more.

A poem published in The Living Wilderness in memory of Zahniser summed up the life of a man who lived and struggled for the “untrammeled,” the voiceless and wild, as well as any words can:

We seedlings in the wild, being imbued with his love of mankind and nature.

Will grow taller and stronger in our loss of mighty oak.

His life gives us new life.

His end is our beginning.

His esthetic values are our values, to hold even dearer at his departure.

His goodness, his beautiful soul, his shining ideals carrying all of us onward and forward...