4 ways protecting lands and waters can help answer the extinction crisis

Cougar in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming/Montana/Idaho

Jacob W. Frank, NPS

Conserving habitat and migration corridors key

Forgive us for sounding like a broken record: The mass extinction crisis is a big deal.

Driven by human activity, it’s shaking the bedrock of nature itself and hurting quality of life for communities worldwide (with consequences that disproportionately impact communities of color and low-income people). And as we pump more climate-warming pollution into the atmosphere and allow the footprint of industrial development to grow ever larger, time is running out to meaningfully address the problem.

We’ve already covered the basics of what the extinction crisis means and how the extinction crisis affects people. So how about solutions?

The logical starting point to address this crisis is to protect lands and waters in a life-support system that will stand as a bulwark against threats here and abroad.

Protecting lands and waters can help address the extinction crisis by...

1)...conserving dwindling habitat

As a result of large-scale agriculture, logging, runaway development and other threats, roughly 9 percent of all land species worldwide do not have enough habitat for long-term survival. This makes sense: if you lose the place you live, you’re going to have a harder time, well, living. But we can help stem the tide and ensure more species survive by conserving the lands and waters they depend on.

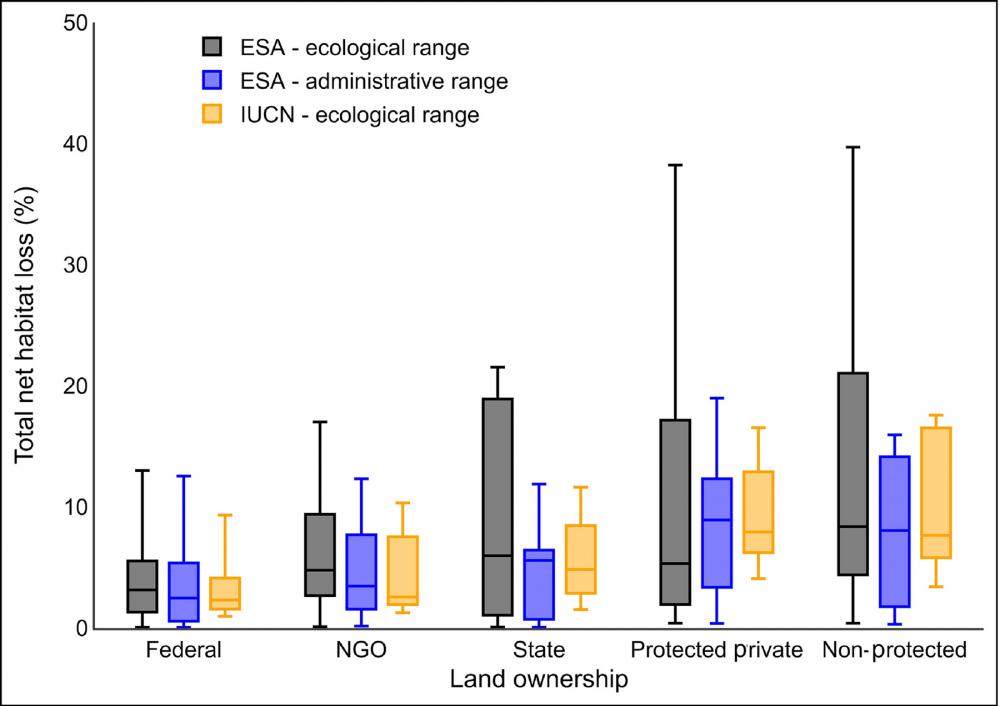

A major body of scientific research already confirms that protecting places with national-level designations—for example, as wilderness areas or national parks—is one of the best ways to get this done. A 2020 analysis of decades’ worth of satellite data found that key endangered and threatened species lost less habitat on federally protected lands than on unprotected or other lands, as illustrated on the chart below that shows total habitat loss for imperiled species in the United States was highest on non-protected lands.

Rates of habitat loss within imperiled species ranges were lowest on federal lands and highest on non-protected private lands.

Eichenwald, et al., 2020, Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment

Those stretches of protected land and water host a greater variety of life, too. A study of global biodiversity data published in 2016 found that there were 10.6 percent more species in protected areas than unprotected areas.

While human development eats up more habitat every day, there is still a lot of wild nature left to conserve: about 60 percent of the continental U.S. is still in a “natural” or wild state. A study published in 2021 by Wilderness Society scientists found that at least 10 percent of suitable habitat for most land vertebrates (mammals, birds, amphibians and reptiles) could be conserved by protecting 30 percent of the continental U.S., paralleling a national conservation goal adopted by the Biden administration.

2)...giving wildlife clear pathways to migrate and adapt

When climate change (or another hazard) makes habitat too hot or otherwise inhospitable, wildlife are forced to pick up and move. But what happens when populations of animals and plants find their escape routes—scientists call them “migration corridors”—cut off by highways, power lines, fences or sprawling development? You guessed it: they may be unable to adapt.

And even if its members manage to hunker down and endure immediate threats, a wildlife population that is blocked from moving and adapting may have its genetic health irreversibly damaged in the long run (if animals from one herd can’t reach members of another herd to reproduce, they’ll end up inbreeding, resulting in weaker and less adaptable offspring).

Maintaining a connected network of protected lands and waters allows wildlife to shuffle around and have a shot at survival. The most valuable such corridors, and the most important to protect, are the places that have been the least altered by development and other human activities. Among other things, ensuring wild, unfettered migration corridors helps make sure wildlife populations are stronger and more able to endure from generation to generation.

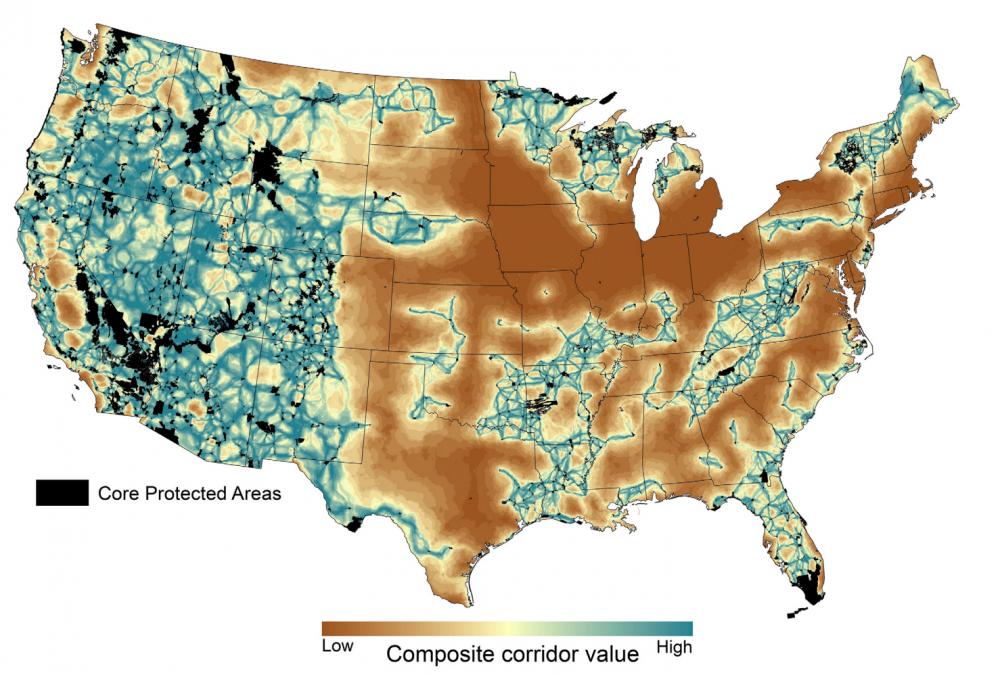

Composite corridor value between large protected core areas

Belote RT, Dietz MS, et al., 2016, PLoS ONE

The map above, developed by Wilderness Society experts, shows some of the wildest and least human-developed “corridors” (blue webbing) connecting core protected areas (black shapes) like wilderness areas or national parks. Protecting such places is key to helping wildlife survive, including in landscapes like the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau, the Southern Appalachians and the Idaho “High Divide” near Yellowstone National Park.

3) ...combating climate change

According to a recent United Nations climate change report, even in moderate warming scenarios, 14 percent of land species will likely face “very high risk of extinction” in the coming years.

Well guess what? Protected public lands serve an important role in confronting the climate crisis. The most familiar example of that is forests (especially old-growth forests), which, if left intact, store climate-warming greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Cutting forests down, on the other hand, exacerbates the climate crisis by releasing that stored carbon.

That’s not the only way public lands factor into climate pollution. Currently, fossil fuel development located on public lands is responsible for almost one quarter of the country’s greenhouse-gas emissions. We could turn public lands into a tool for confronting climate change by drawing down that development and prioritizing cleaner renewable energy projects instead.

4) ...protecting biodiversity “hot spots”

By now, you’ve probably heard or read something about the need to protect “biodiversity.” More than just conserving one population or species, this refers to conserving the full variety of Earth’s life at all levels, from genes within an individual creature up to entire ecosystems. Because the current mass extinction is affecting life on all those (interconnected) levels, it may also be called something like “the biodiversity crisis” or “global biodiversity loss.” All these terms boil down to the same thing: animals and plants dying out at an accelerated rate, mostly caused by human activity (and spelling major consequences for people worldwide).

The same way saving places wildlife need also requires shoring up the corridors between tracts of land, we must protect places that can help preserve not just a single population or species, but further the goal of protecting biodiversity at large. Biodiversity “hotspots” are places with lots of species found nowhere else, and they have outsized conservation value. By protecting just 25 global biodiversity habitats we could help save 44 percent of vascular plant species and 35 percent of all species of mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians. Research suggests that preserving those places helps reduce extinction risk in individual species.

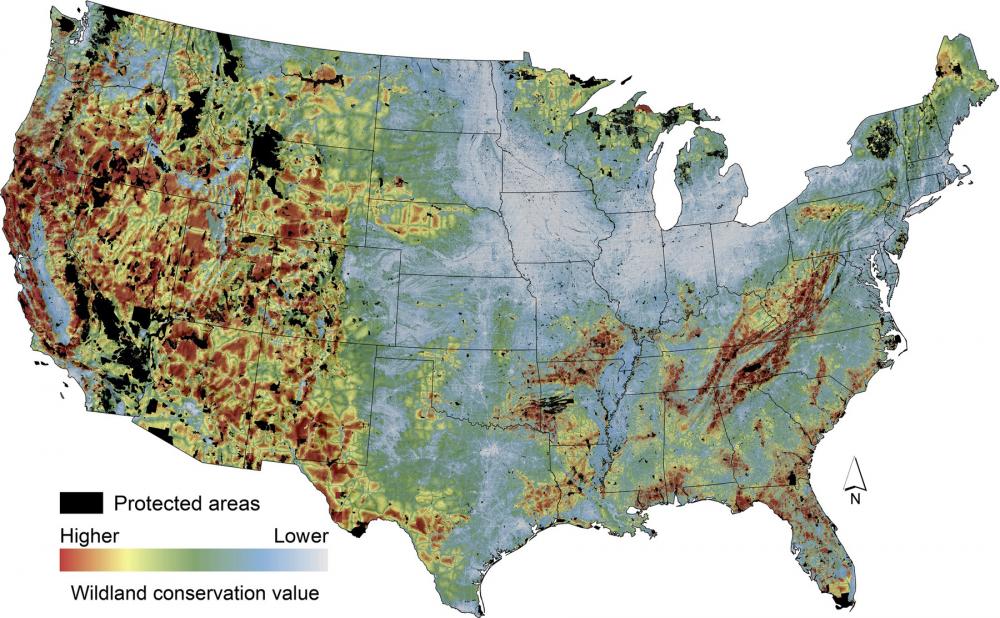

The Wilderness Society map below shows parts of the U.S. that are top priorities to protect if we want to preserve species. There are many different ways to measure biodiversity priority; the red areas are places where the most criteria for conservation priority are met, including species richness (the number of different species present) and rarity of species.

Composite map of wildland conservation value

Belote, Dietz, Jenkins, McKinley, Irwin, Fullman, Leppi, Aplet, 2017, Ecological Applications

These are some of the key places we should concentrate on protecting within the larger goal of conserving a network of 30 percent of lands and waters—the places containing significant habitat for the most different kinds of plants and animals.