5 disastrous consequences of Trump admin’s final Bears Ears and Grand Staircase plans

Bears Ears National Monument, Utah

Mason Cummings, TWS

Monuments’ cultural sites, fossils, ecosystems under threat

Though legal challenges to President Trump’s unlawful attacks on Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante continue to advance in court, the Bureau of Land Management and Forest Service have now released their final plans for how to manage the fraudulent and hugely diminished versions of Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monuments.

Among other activities, the Trump administration is looking to develop roads and infrastructure throughout the monuments, tear up plant life and increase visitor traffic to sensitive cultural areas with no clear plans for increasing security.

Here are just a few of the disastrous consequences we can expect from these plans.

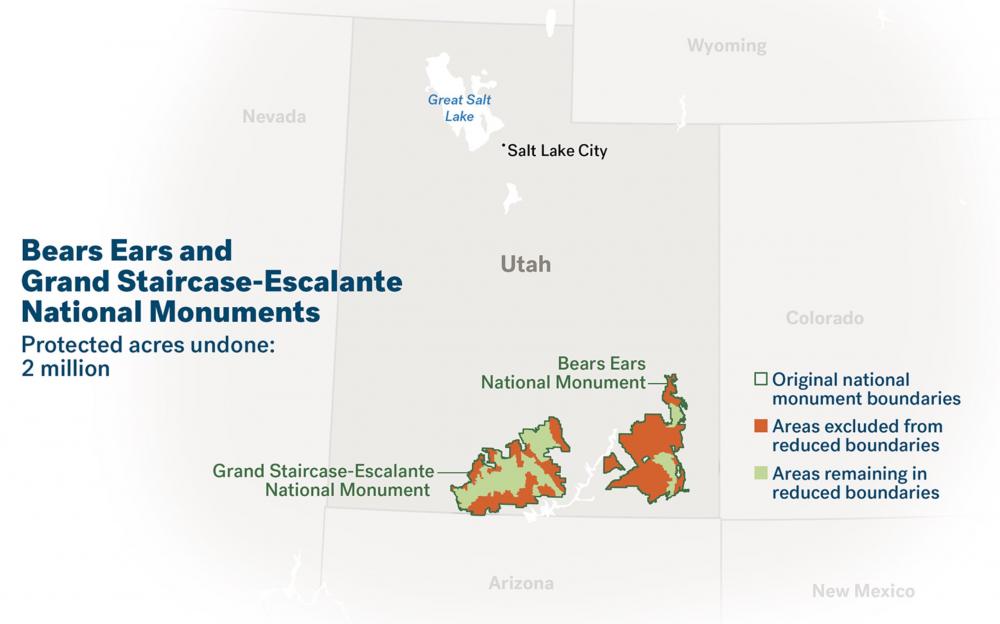

Map showing original extent of Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments and revised protections after Trump's rollbacks

TWS

1. Rock art, cliff dwellings and other culturally significant sites will be left open to looting and damage

In Bears Ears, the final monument plan released by the BLM appear to lay out guidelines for protecting cultural sites. But those guidelines are based on scant information, as most of the land area in the monuments hasn’t even been surveyed yet.

Dangerously, these plans lay the groundwork for increased visitor traffic at a number of cultural sites without a clear strategy to add resources and police activity at those sites. These include old cliffside dwellings; rock art panels; partly excavated ceremonial buildings called kivas; and the Hole-in-the-Rock Trail, a historic Mormon pioneer site. Many of these same spots have already been hit hard by visitor misbehavior.

Take Butler Wash, a stretch of sandstone terrain along the eastern edge of the so-called Shash Jáa Unit. Previously, target-shooters have marred rock art in Butler Wash with bullet holes, and in 2013, a burial site was desecrated by looters. Yet the broader Butler Wash area contains three sites designated for increased public use in the new plans.

In one of the most distressing examples of new damage that could result from these plans, target shooting will “generally” be permitted in Bears Ears. The activity has been a major problem in historical and cultural sites in Utah.

The administration is paving the way for reckless behavior that will deal yet another unforgivable blow to the Navajo, Hopi, Ute Mountain Ute, Zuni and Ute Indian Tribe peoples who petitioned for protection of Bears Ears as a national monument in the first place.

2. Fossils will be vulnerable to “casual” collection and potentially destroyed

The new plans would open more areas with high fossil potential to impacts from off-highway vehicles, grazing and development—plus “casual” collection by visitors. These guidelines imperil some of the nation’s most significant sources of fossils.

In Grand Staircase-Escalante, which has yielded at least 25 new dinosaur species and contains an estimated 3,000 “scientifically important” fossil sites, the management plan allows for casual collection of fossils on nearly all lands Trump removed from the monument. Meanwhile, in Bears Ears, which is better known for its archaeological resources but has still offered up a number of notable fossil specimens, the plans would allow increased visitor traffic at places like the dinosaur track site at Butler Wash without any concrete strategies for policing visitor activity.

It’s not hard to see how an ‘open the floodgates’ approach to crowd control at such a site might lead to under-supervised resources being vandalized or accidentally damaged. Some Bears Ears sites with high fossil potential will even be opened to “limited” off-highway vehicle activity.

3. Plants (and the broader ecosystem) will be torn apart

It would be bad enough if ‘only’ Bears Ears’ and Grand Staircase-Escalante’s cultural and scientific resources were at risk, but the lands themselves will also suffer as a result of the new plans. One of the most visceral examples of the damaging activities allowed under the new plans is “chaining.”

“Chaining” is when a pair of bulldozers, tractors or other vehicles drag an enormous chain (typically 250 to 300 feet long and weighing as much as 16,000 tons) across the terrain in order to uproot trees and other plants.

Think of a fishing boat using a big net to trawl along the seafloor. The chains are intended to scour the land and denude it of life in order to make way for livestock grazing (in Bears Ears’ case, chaining and other methods would likely be used to tear up acres of native piñon-juniper forest). But the process has been linked to a range of terrible consequences. For example, research has found that chaining can allow troublesome species like cheatgrass to invade the treated site.

By pulling out deep-rooted trees and shrubs, chaining may also weaken the stability of some slopes and cause more erosion and landslides. The machinery involved with mechanical treatments can be extremely destructive to biological crusts that form the substrate of ecosystems.

4. Mining and drilling will scar a unique southwestern landscape

By advancing a final plan for Bears Ears that completely ignores the 85% of the lands that President Trump illegally removed from protections, the plans completely neglect to provide any protections against new mining claims, fossil fuel leasing and other mining and drilling development in these areas – despite the reductions being challenged in court. This follows documented efforts by uranium mining interests to lobby for reductions to the monument during the Trump Administration’s sham “review.”

In Grand Staircase-Escalante, hundreds of thousands of acres called the Kanab-Escalante Planning Area—the area Trump unlawfully cut from Grand Staircase-Escalante--would be opened to mining and drilling. This could mean thousands of acres dug up and stripped, waterways polluted with soil and contaminants and wildlife driven away by dust and noise pollution. Previously, local business owners and outdoor recreationists raised concerns about mining’s impacts on tourism, which has been a huge part of the region’s economy since the monument was established in 1996.

The fact that the plans would introduce mining to the area only reinforces that Trump's monument attacks were likely motivated by a push to drill and mine all along. In 2018, we produced maps that show how cuts to Grand Staircase-Escalante paved the way for coal, oil, gas and tar sand development in many areas that have enormous potential for fossil finds that could advance scientific understanding of how species evolved.

5. New roads and off-road vehicles will carve up the landscape

The land Trump illegally cut out of Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments would remain public, but it will no longer enjoy full protections from degradation – if these illegal actions are allowed to stand. One of the most immediate concerns is re-opened roads and reckless off-highway vehicle (OHV) use. Motorized vehicles may now be allowed on any road that existed prior to the establishment of the monuments--and that may end up being hundreds of roads, including places that don't look much like roads at all. Tribal artifacts and fossils could suffer as a result of this intrusion.

In Bears Ears, plans would recognize San Juan County’s off-highway vehicle (OHV) route system and integrate it in the official management of the monument. This would likely be the precursor to the designation of additional off-road areas in Bears Ears.

In Grand Staircase-Escalante, the final plans would allow off-road vehicles to drive on routes through wilderness study areas. Additionally, a 2,528-acre area called Little Desert would be designated for travel off-route and three new roads have been proposed for construction.

Bears Ears National Monument, UT

Mason Cummings, The Wilderness Society