Our History

Since 1935, we’ve been protecting wilderness and inspiring Americans to care for our wild places. The Wilderness Society has led the charge to protect 111 million acres of wilderness since our founding and we’ve directly contributed to the passage of almost every major conservation law while fighting hard against attempts to undermine them. We’re humbled by how much work is still left to do, but incredibly proud of our tradition.

1935-1956

Birth of a movement

The Wilderness Society was founded in 1935, an "organization of spirited people who will fight for the freedom and preservation of the wilderness." In the years that followed, we worked with conservationists at large to rally around a few big causes such as preventing a destructive dam from being built on the Dinosaur National Monument's Green River in the 1950s. These battles over individual development threats soon led to a focus on permanently protecting a select few fragile landscapes like the Arctic Refuge, and an effort to build a unified, national framework for protecting the wildest places.

The Wilderness Society

1935: The Wilderness Society is founded

A group of visionaries--Aldo Leopold, Robert Marshall, Robert Sterling Yard, Benton MacKaye, Ernest Oberholtzer, Harvey Broome, Bernard Frank and Harold C. Anderson--form The Wilderness Society to save some of America’s dwindling wildlands. At the time, forests and other public lands are mainly seen as resources for logging, mining and other development. Setting out to conserve the wildest places is a revolutionary idea.

Learn moreOil Drilling: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

Mason Cummings, TWS

1953: Defending America’s wildest frontier

Wilderness Society President Olaus Murie, activist Mardy Murie and others begin working to permanently protect the northeastern corner of Alaska, which is already being called “the last great wilderness.” Seven years later, President Dwight D. Eisenhower will follow their lead by protecting the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. The campaign to preserve those rugged wildlands as-is and independent of manmade activity ends up directly informing the creation of the Wilderness Act.

The Wilderness Society

1956: First draft of the Wilderness Act written

A Pennsylvania-born Wilderness Society leader named Howard Zahniser writes the first draft of legislation to protect wilderness areas across America. Over the next eight years, Zahniser’s bill will be rewritten or resubmitted 66 times and subject to 18 public hearings and 16,000 pages of testimony.

Learn more1964-1978

New era of progress

The optimism and innovation of the 1960s brought with it many conservation successes. Several major laws championed by The Wilderness Society established the language and ideas that still inform public land protection in America, highlighted by the Wilderness Act of 1964, which was written by a Wilderness Society leader.

Conservation: Wilderness in New Mexico

Mason Cummings, TWS

1964: Our proudest moment arrives with passage of the Wilderness Act

President Lyndon Johnson signs The Wilderness Act to create a way for Americans to protect their most natural and unspoiled wildlands for future generations. The act immediately puts 9.1 million acres of land into the National Wilderness Preservation System and sets the framework for decades of wilderness conservation. Known for its poetic vision of dwindling “untrammeled” lands, the bill was written and championed by The Wilderness Society’s own Howard Zahniser, who had since passed away. Alice Zahniser, his widow, and Mardy Murie, the widow of former Wilderness Society President Olaus J. Murie, were the White House’s guests at the bill-signing.

The Wilderness Society

1976: First woman to lead a national conservation group

Celia Hunter, a fiercely dedicated advocate for public lands protection in Alaska and nationwide, is named the president of The Wilderness Society after several years on its Governing Council. She is the first woman ever to head up a national conservation group.

Learn moreRoad Building: Gates of the Arctic National Park

Mason Cummings/TWS

1978: President Carter protects Alaska wildlands

After a decades-long campaign by Wilderness Society council member Mardy Murie to protect wildlands in her beloved Arctic, President Jimmy Carter designates 15 new national monuments in Alaska under the Antiquities Act, taking action to defend wildlands after Congress cannot. At the time, it’s the largest public lands protection yet undertaken by a president and is later credited with helping lawmakers realize the need to work together on protecting lands.

1980-2001

Challenges demand ambitious approach

Just before leaving office, President Jimmy Carter protected over 100 million acres of wildlands in Alaska, delivering on what had been a focus of The Wilderness Society for decades. But the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s brought many new political challenges and threats to public lands. The Wilderness Society responded with bulked-up legal and legislative efforts and new initiatives like the Wilderness Support Center, established in 1999 to marshal grassroots support for important land-protection legislation.

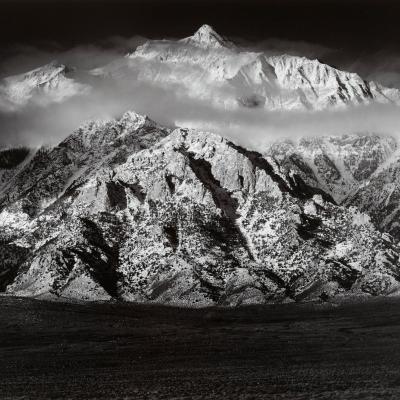

Ansel Adams

1980: Legends of conservation

Legendary landscape photographer Ansel Adams receives a namesake award from The Wilderness Society for his decades of advocacy and as editor for The Living Wilderness. He is part of a leadership era that includes conservation legends like Earth Day founder Gaylord Nelson, renowned western writer Wallace Stegner, “grandmother of the conservation movement” Mardy Murie and Stewart Brandborg, who helped shepherd the Wilderness Act to final passage.

Learn moreConservation: California Desert

Mason Cummings, TWS

1994: Major law protects Joshua Tree and other wildlands

After nearly a decade, an ambitious campaign by The Wilderness Society to protect Joshua Tree, Death Valley and other wildlands in the California desert culminates with the California Desert Protection Act of 1994. The bill, which directly grew out of a proposal by The Wilderness Society and other groups, is the most far-reaching wilderness protection law ever passed in the lower 48 states.

Nelson Guda

2001: Roadless Rule protects our wildest forests

The U.S. Forest Service adopts the Roadless Area Conservation Rule, establishing that road construction, timber harvesting and other development should not be allowed in the very wildest parts of our national forests. The Wilderness Society had been advocating for protection of roadless forests for decades, and banded together with other groups in the 1990s to drive public involvement and directly influence policymakers to that end.

2009-2017

New conservation standards set

The Wilderness Society played a leadership role in a bold era characterized by protection of big, wild landscapes and the start of inward-looking efforts to build a more diverse conservation community. The growing body of science on the threats posed by climate change drove us to broaden our scope, including by pioneering initiatives to take stock of previously ignored greenhouse gas emissions resulting from energy production on federal lands and waters.

National Monuments: San Gabriel Mountains

Michael Gordon

2009: 2 million acres of wilderness protected in a major victory

The Wilderness Society successfully pushes Congress to pass one of the largest expansions of wilderness protections in 15 years. The Omnibus Public Land Management Act permanently protects more than 2 million acres of unspoiled American wilderness in California, Colorado, Idaho, Michigan, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Virginia and West Virginia. We have now helped protect more than 111 million acres of wildlands since our founding.

Bob Wick, BLM

2016: Our Commitment to Diversity, Equity and Inclusion

We officially launch our Commitment to Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at The Wilderness Society. This means a renewed effort to ensure our work reflects cultures and perspectives of people and communities across our nation, and a commitment to helping all people, regardless of background, be able to know and enjoy our public lands.

Learn moreNational Monuments: Bears Ears

Mason Cummings, TWS

2017: A monumental legacy

The Wilderness Society successfully advocates for President Obama’s expansion of the California Coastal and Cascade-Siskiyou national monuments, capping off a presidency of remarkable conservation accomplishments that included 34 designations or expansions of national monuments. President Obama also protected numerous places The Wilderness Society identified as "Too Wild to Drill" and worked to defend, including cancelling most of the remaining oil and gas leases in the Badger-Two Medicine area of Montana and blocking new drilling in much of the Arctic Ocean.

2017-2020

Standing up to unprecedented threats

Shortly after President Barack Obama completed his term in office, having worked with The Wilderness Society and other partners to protect more lands and waters than any other president, the election of Donald Trump dealt conservation a harsh blow. In his first year, Trump unlawfully gutted protections for Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments. The WIlderness Society helped rally opposition to those actions, which were likely the biggest attack on public lands in modern history. As we move into a new defensive era, the backlash to the Trump administration is helping to inspire a new interest in public lands among Americans of all stripes and renewed recognition of the need to defend them.

2021-NOW

A new era addressing climate change and environmental justice.

We will work on undoing the damage by the Trump Administration and move forward as we focus our work on addressing the climate crisis and environmental justice.