Happy birthday to Aldo Leopold, wilderness pioneer

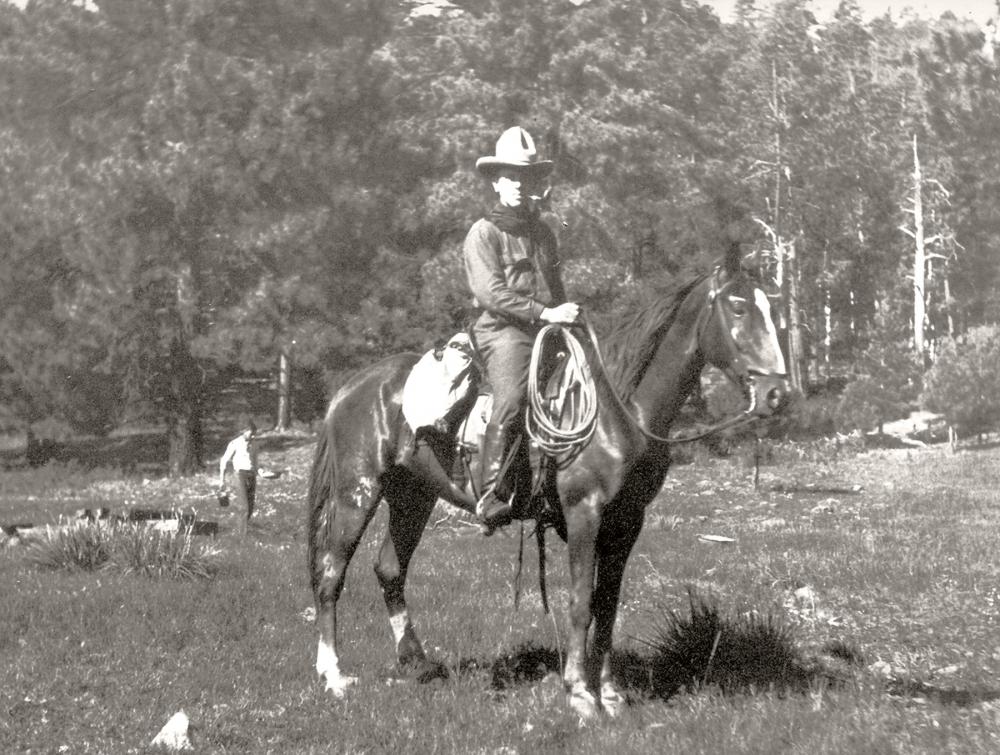

Aldo Leopold

The Wilderness Society

Leopold co-founded The Wilderness Society in 1935

Jan. 11 marks The Wilderness Society co-founder Aldo Leopold’s birthday. We celebrate the life and vision of a seminal American conservationist.

Aldo Leopold co-founded The Wilderness Society in 1935, but his influence stretches far beyond that.

Leopold is probably best-known for his concept of the “land ethic”--loosely, the notion that mankind’s idea of community, and the mutual respect it both engenders and requires, should be extended to plants, animals and the earth itself. This informed his prolific life in conservation, including the cause of wilderness protection--and even extended to the house he designed and builtas a young man.

Born near Burlington, Iowa, in 1887, Leopold spent his boyhood exploring woods, prairies and other wild spots along the Mississippi River, nurturing what would be a life-long love of nature. He graduated from Yale in 1909 with a Master of Forestry degree and went to work for the U.S. Forest Service in Arizona’s then-newly-established Apache National Forest.

After several years of working mostly within that agency, whose focus at the time was primarily timber management, Leopold recognized that there was an urgent need to preserve some of the nation’s dwindling wildlands. In 1922, he submitted a formal proposal that Gila National Forest, in western New Mexico, be managed as a wilderness. In 1924, the Gila Wilderness was officially established there, becoming the first protected wilderness area in the U.S. (and perhaps the world). The process of protecting wilderness has changed significantly in the nine decades since--in large part due to the passage of The Wilderness Act in 1964, which set an official framework for managing and designating wilderness areas--but the concept of protecting special public lands at a high level was pioneered by Leopold among a select few.

Leopold later laid out the importance of the land ethic in a collection of essays on nature and his farm in Wisconsin that was collected as A Sand County Almanac. Published after his death, that book became an essential American work on the environment and how to live responsibly within it. Perhaps its most immortal line: “There are some who can live without wild things, and some who cannot. These essays are the delights and dilemmas of one who cannot.”

Many years later, this idea still drives our work: The Wilderness Society cannot live without wild things!

Happy birthday, Mr. Leopold.