The Wilderness Hall of Fame: 13 presidents who were conservation leaders

These are the White House’s most prominent champions of public lands ever

In Washington DC, parks, forests and refuges—and the very idea of "Our Wild"—face truly harrowing challenges. The Trump regime has already unveiled a host of anti-conservation policies, pandering to special interests and working with ideological allies in Congress to roll back some of President Obama's greatest accomplishments, including deep cuts to Bears Ears National Monument.

Meanwhile, ordinary Americans value their wild heritage as much as ever. Polling has shown that about 90 percent of voters nationwide support permanent public land protection (while 69 percent oppose measures to prevent it). Even in what seems to be an unusually political and polarized age, the value of Our Wild is all but universal. In a survey conducted after the 2016 election, most Trump voters said they oppose efforts to privatize or sell off public lands. Millions of Americans submitted comments to the Trump administration opposing its punitive review of national monument lands.

Now more than ever, strong political leadership is critical. One of the clearest exercises of such leadership is the Antiquities Act—a law authorizing presidents to protect special places as national monuments if Congress won’t. Our nation’s history is full of great presidents who used it and other tools at their disposal in the name of conservation.

Given the climate in Washington, we feel it is important to salute the greatest among them. By our admittedly subjective criteria, incorporating both the conservation standards of their times and the precedents set by their administrations’ words and deeds, these are the White House’s most prominent champions of public lands.

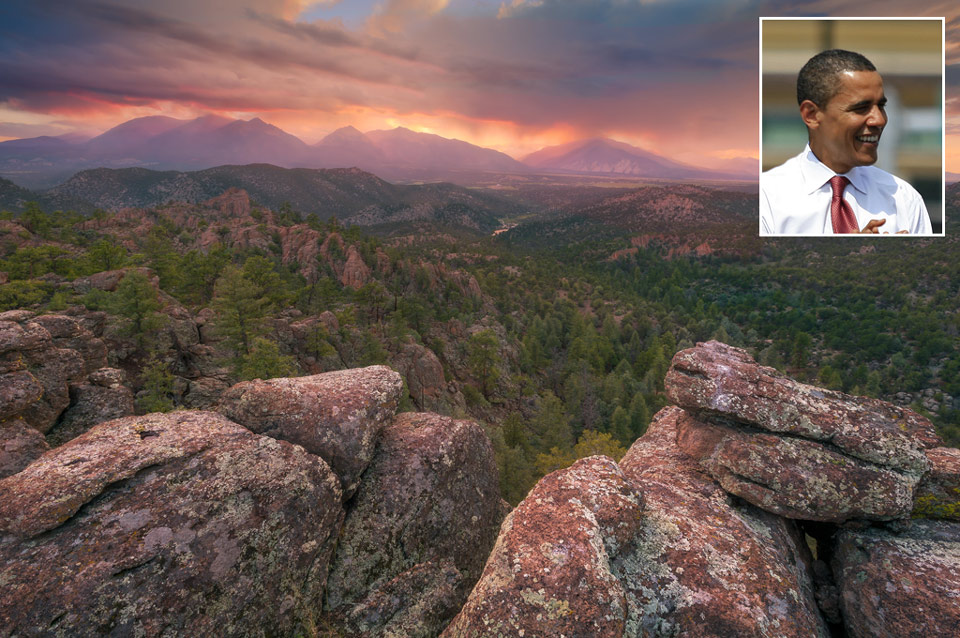

Barack Obama (2009-2017)

Photo credit: Browns Canyon National Monument - Mason Cummings, The Wilderness Society; Obama - Robbie Wroblewski, flickr

President Barack Obama's plaque for the Wilderness Hall of Fame has to start with this: he protected more lands, waters and cultural sites than any other president, culminating with the Gold Butte (Nevada) and Bears Ears (Utah) national monuments and the expansion of the California Coastal and Cascade-Siskiyou (Oregon) national monuments.

In addition to safeguarding wild landscapes, President Obama has a remarkable record of diversifying our parks and public lands by recognizing the contributions of traditionally underrepresented groups. He designated the first monument dedicated to LGBTQ rights and also used the Antiquities Act to salute the civil rights, labor and women's suffrage movements.

As the threat of climate change became ever more urgent, President Obama met the challenge head on. He committed the U.S. to reduce greenhouse gas emissions under the Paris climate accord; pioneered the Clean Power Plan to reduce emissions from coal-fired power plants under the Clean Air Act; and even released a rule to reduce methane pollution from oil and gas operations on public lands.

President Obama also recognized that some places are simply "Too Wild to Drill." He undertook historic actions to finally cancel most of the remaining oil and gas leases located in the Badger-Two Medicine area of Montana's Rocky Mountain Front, cancelled many leases in Colorado's Roan Plateau and Thompson Divide and even blocked new drilling in much of the Arctic Ocean.

As if all that wasn't enough, President Obama sought to help his fellow citizens connect with nature. His Every Kid in a Park initiative, which was recently extended beyond his presidency, aims to get more kids playing and learning outdoors by providing 4th grade students and their families free admission to all national parks and other federal lands and waters.

Put simply, few presidents—if any—have done as much as President Obama did to safeguard our planet and our country for future generations. He is a thoroughly deserving inductee into the Wilderness Hall of Fame, and a figure whom other leaders present and future would do well to emulate.

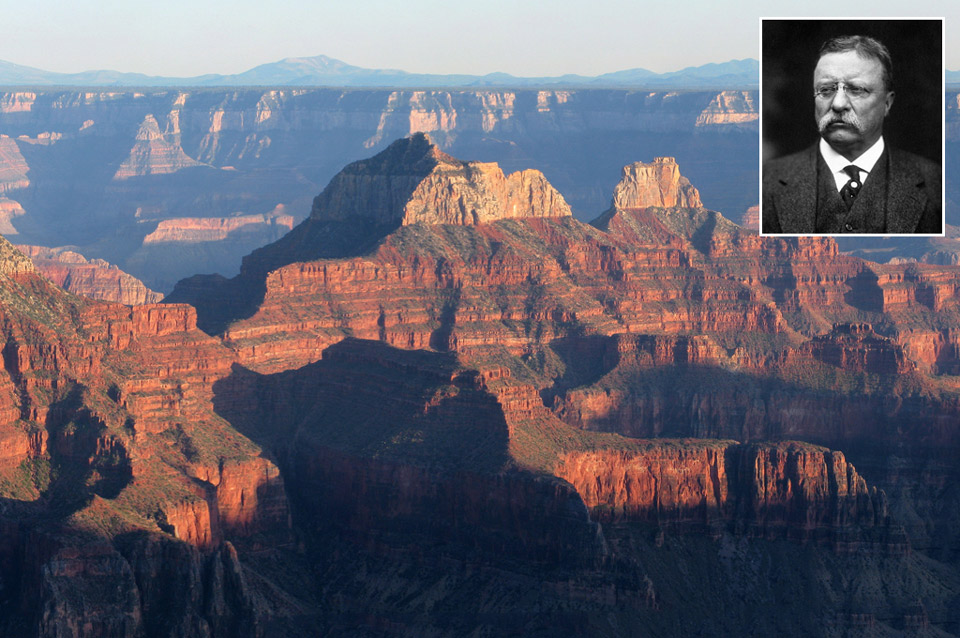

Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909)

Photo credit: Grand Canyon National Park - Michael Quinn, National Park Service, flickr; Roosevelt - Pach Brothers, Wikimedia Commons

The consummate sportsman-cum-scholar, “Teddy” Roosevelt’s energetic commitment to the wild may be best exemplified by his famous words before designating the country’s first national wildlife refuge in Florida in 1903. Concerned that brown pelicans in the area were being overhunted, the president asked an aide, "Is there any law that will prevent me from declaring Pelican Island a federal bird reservation?” Told that there was not, Roosevelt, ever direct, reportedly snapped “very well, then I so declare it.”

It was not the first time the government had protected land, but it set in motion a pattern of active natural stewardship that echoed over the next century. Roosevelt’s administration went on to establish more than 50 more bird reservations; preside over the creation of the National Forest Service and massive expansion of forest reserves; and sign the Antiquities Act into law, granting presidents the authority to protect natural and cultural landmarks as national monuments when Congress would not or could not get the job done (Roosevelt would use this method 18 times).

In all, the 26th president set aside over 230 million acres of land for conservation. Fittingly, more National Park Service units have been dedicated to him than any other American. Roosevelt’s acts in the service of wilderness could—and have—filled many volumes, and no list of White House conservation champions could credibly include any name other than his at the top.

Lyndon B. Johnson (1963-1969)

Photo credit: Uncompahgre Wilderness - Bob Wick, BLM, flickr; Johnson - U.S. Embassy New Delhi, flickr

Though he spent only one elected term as the nation’s chief executive, Lyndon Johnson left an indelible mark on America’s public lands heritage. Within one year of taking office, he signed the Wilderness Act into law in 1964, establishing the framework to protect exceptional public lands at the highest level possible. That law immediately put 9 million acres of wild American lands into the National Wilderness Preservation System, and has since protected 100 million more.

If that had been his only conservation accomplishment, it would have sufficed—but President Johnson went on to establish the National Trails System and sign into law the Endangered Species Preservation Act and Land and Water Conservation Act. The latter, originally proposed by John F. Kennedy for the protection and upkeep of public lands, authorized a fund that has since helped add lands to Grand Canyon and Rocky Mountain national parks along with many other parks, refuges and forests.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1933-1945)

Photo credit: Olympic National Park - javi.velazquez, flickr; Roosevelt - FDR Presidential Library & Museum, flickr

Franklin Delano Roosevelt is not as closely associated with conservation as his cousin Theodore, but he was still among the greatest champions of public lands our nation has ever known.

Fittingly, his most prominent accomplishment in that vein was part of the domestic initiative that made him a hero to generations of Americans. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), one of the first enacted programs of the New Deal, put millions to work building infrastructure in national parks and forests, ultimately planting billions of trees and combating soil erosion on 84 million acres of farmland.

A lover of nature and wildlife since his youth, Roosevelt also undertook many executive actions to protect public lands in the face of intense congressional opposition. Using the Antiquities Act, Roosevelt significantly expanded Dinosaur National Monument (originally designated by Woodrow Wilson) and created Joshua Tree National Monument (later a national park) and 10 others.

Less directly, his decision to explore the wilds of the Washington peninsula for himself led to a popular campaign to set aside land as Olympic National Park “to conserve and render available to the people, for recreational use, this outstanding mountainous country,” despite an uproar from industrial interests. In this and other conservation initiatives, Roosevelt was aided by his crusading Interior head, Harold Ickes, who helped desegregate both the culture of that agency and the public lands of the American south.

Benjamin Harrison (1889-1893)

Photo credit: Katmai National Park - Mark Stevens, flickr; Harrison portrait - Political Graveyard/Portrait and Biographical Album of Washtenaw County, Michigan, 1891, flickr

Like most presidents on this list, Benjamin Harrison’s protection of wild places can be attributed at least partly to an active, outdoor childhood. Fittingly, he was one of Theodore Roosevelt’s political heroes, and despite spending only a short time at the country’s helm, he had a significant impact on public lands stewardship.

Prior to his presidency, Harrison was a dogged wilderness champion in the Senate, repeatedly pushing for legislation to limit development in Yellowstone and becoming the first to introduce a bill to create Grand Canyon National Park, variations of which he repeatedly tried to pass thereafter. Once in the White House, he issued an executive order to create the Afognak Island Forest and Fish Culture Reserve in Alaska, today part of Katmai National Park and Preserve, to be “protected and preserved unimpaired.” Though the Grant administration is credited with the first federal land protection undertaken for wildlife, some consider Afognak, which was set aside largely to safeguard salmon, to be effectively one of the first true national wildlife refuges. That same year, Harrison ordered the creation of the Casa Grande Ruin Reservation in Arizona, “the first prehistoric and cultural site to be established in the United States.”

The Forest Reserve Act of 1891, promoted by Harrison-era Interior Secretary John Noble and signed into law by Harrison himself, directly led to the preservation of 13 million acres, including America's first forest reserve in Yellowstone. Even more significantly, its provision allowing future presidents to establish forest reserves and empowered many wilderness champions to come.

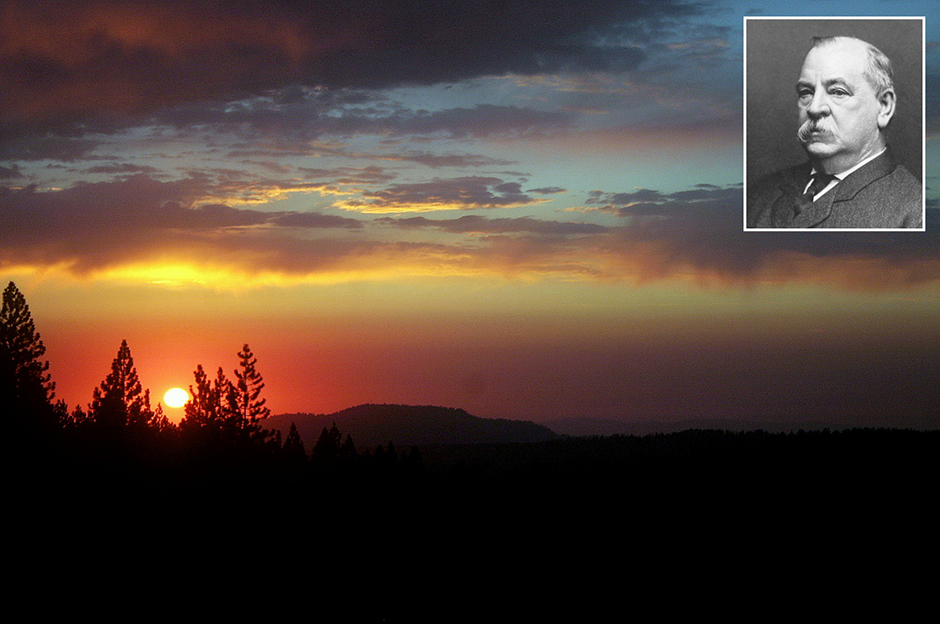

Grover Cleveland (1885-1889, 1893-1897)

Photo credit: Stanislaus National Forest - Alice Poulson, USFS Region 5, flickr; Cleveland portrait - General Services Administration, Wikimedia Commons

Though Grover Cleveland unseated Benjamin Harrison in winning the second of his non-consecutive presidential terms, he faithfully continued many of his predecessor’s conservation policies.

Using Harrison’s Forest Reserve Act, President Cleveland inducted millions of wooded acres into the forest reserve system. The most famous of these were 13 new or expanded reserves protected in the final days of his second term, enraging timber tycoons, who dubbed them “Midnight Reserves” (conservationists called them the “Washington’s Birthday Reserves”). Earlier, in reaction to lackluster policing of poachers in Yellowstone and resultant outcry by the Theodore Roosevelt-founded Boone and Crockett Club, Cleveland signed into law the Act to Protect the Birds and Animals in Yellowstone National Park. The 24th president, a proud reformer renowned for his common-sense approach to governing, reportedly boasted of his accomplishments in the service of public lands well into his post-presidency years.

Jimmy Carter (1977-1981)

Photo credit: Wrangell-St. Elias National Park - Bryan Petrtyl, NPS, flickr; Carter portrait - Department of Defense/Department of the Navy, Wikimedia Commons

In January of 1978, President Jimmy Carter designated 15 new national monuments in Alaska, acting where Congress would not. This action was credited with helping wilderness opponents realize the need for compromise on public lands legislation, and proves a pointed lesson for a modern climate of political discord.

Carter wasn’t done yet; the next month, the president signed into law the Endangered American Wilderness Act, which then represented the largest single addition to our National Wilderness Preservation System since 1964. In 1980, just before leaving office, Carter signed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act into law, protecting over 100 million acres of Alaskan land in one fell swoop. Even since his stint as president, Carter has continued to be an outspoken advocate for wilderness, especially the “last frontier” of Alaska.

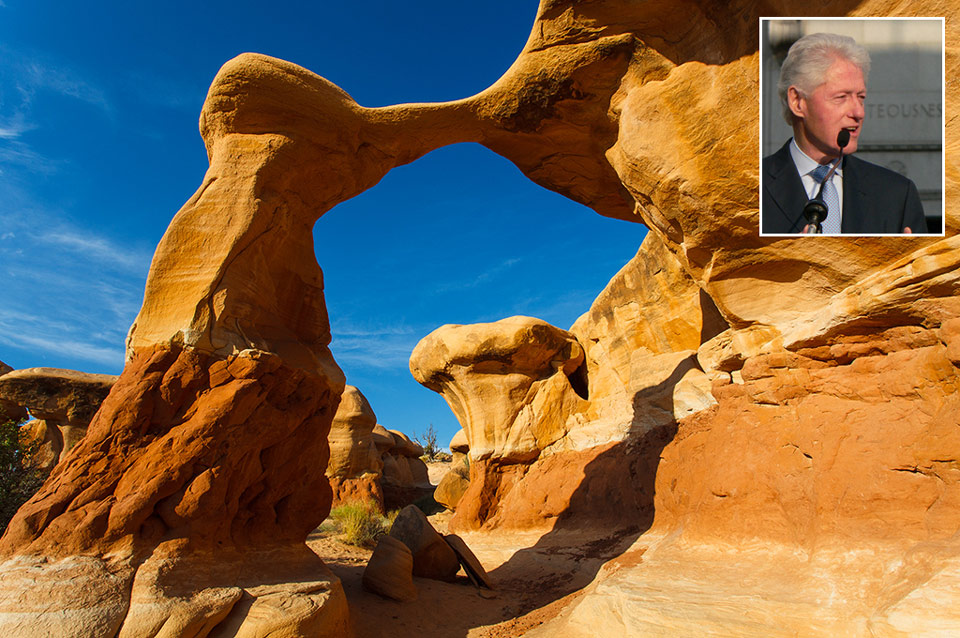

Bill Clinton (1992-2000)

Photo credit: Grand Staircase-Escalante - James Marvin Phelps, flickr; Clinton - victoriabernal, flickr

Following Jimmy Carter’s series of monument designations in 1978, the Antiquities Act fell into disuse for years. However, when the White House started exercising it again, it more than made up for lost time.

During Bill Clinton’s administration, more than 20 national monuments were expanded or added to the register, including Utah’s Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, and California’s Pinnacles National Monument (now Pinnacles National Park) and Giant Sequoia National Monument. In all, his administration protected nearly 27 million acres of public lands. Near the end of Clinton’s time in office, he instituted the “Roadless Rule,” which protected one-third of national forests from roads, development and logging. Though the rule has been attacked repeatedly since then by anti-conservation interests, several high-profile court decisions have upheld it.

Ulysses S. Grant (1869-1877)

Photo credit: Yellowstone National Park - Craig Elliott, flickr; Grant portrait - Matthew Brady, Wikimedia Commons

A military legend whose accomplishments in the White House are sometimes given short shrift, Ulysses S. Grant was another hero of young Theodore Roosevelt—who considered him the “father of the national parks,” per biographer Douglas Brinkley—for a reason.

An expedition to Yellowstone undertaken at the insistence of Grant’s Interior Department led to legislation establishing it as the country’s first national park, which Grant himself signed into law in 1872. More obscurely, the 18th president pushed for the protection of northern fur seals on Alaska’s Pribilof Islands, an action that is considered the first time an area of federally owned land was set aside specifically for wildlife. In many ways, Grant’s administration ushered in the era of presidents who recognized the importance of public lands in their own right.

John F. Kennedy (1961-1963)

Photo credit: Cape Cod National Seashore - Ralph Tiner, USFWS Northeast Region, flickr; Kennedy - University of Michigan School of Natural Resources & Environment, flickr

John F. Kennedy was gifted with only a few years in office before his life was tragically cut short, but he built a strong conservation legacy. His establishment of Delaware’s Prime Hook National Wildlife Refuge under the authority of the Migratory Bird Conservation Act after a clash with that state’s governor showed he was not afraid to use the power of the office for the betterment of conservation, and some of his ideas were well ahead of their time: years before its passage, Kennedy spoke out in favor of a Youth Conservation Corps to “preserve our forests, stock our lakes and rivers, clear our streams and protect America's abundance of natural resources,” and, in the last year of his presidency, he proposed legislation to establish the Land and Water Conservation Fund, a program that reinvests some royalties from offshore oil and gas leases into public lands conservation. Later guided through Congress and signed into law by his successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, it has supported tens of thousands of park projects and protected millions of acres of land—including Cape Cod National Seashore, an area beloved by the Kennedy family.

Thomas Jefferson (1801-1809)

Photo credit: Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge - USFWS Mountain Prairie, flickr; Jefferson portrait - Rembrandt Peale, Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Jefferson’s spot on this list is assured by one deed alone: his commission of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to blaze a path west, surveying exotic plants, animals and landscapes then largely uncatalogued. The travel journals they kept, filled with tales of bison, grizzly bears and dramatic mountain peaks, helped trigger an enduring American fascination with wilderness.

It is fitting that the expedition was initiated by a nature-lover and day-to-day man of science. While conserving natural resources was anathema to his contemporaries, Jefferson prefigured movements to come in 1806, writing of his property, "We must use a good deal of economy in our wood, never cutting down new, where we can make the old do."

Despite his interest in cultivated land and determination to survey and appraise every corner of the country, another quote attributed to Jefferson opined on the virtues of uninhabited spaces as well: “our governments will remain virtuous for many centuries; as long as there shall be vacant lands in any part of America. When they get piled upon one another in large cities, as in Europe, they will become corrupt as in Europe.”

Abraham Lincoln (1861-1865)

Photo credit: Yosemite National Park - Daniel Parks, flickr; Lincoln portrait - Matthew Brady/Marion Doss, flickr

In 1864, Abraham Lincoln signed into law a bill setting aside the Mariposa Grove and Yosemite Valley to be administered by the state of California for "public use, resort, and recreation." As the nation was roiled by some of the bloodiest fighting of the Civil War, this news garnered little attention. However, it set a significant precedent: scenic land could suddenly be set aside for the enjoyment of future generations. At a time when the idea of public parks, let alone protected wilderness, was incredibly remote, this was a major development. Lincoln also founded the Department of Agriculture, later to include various iterations of the U.S. Forest Service.

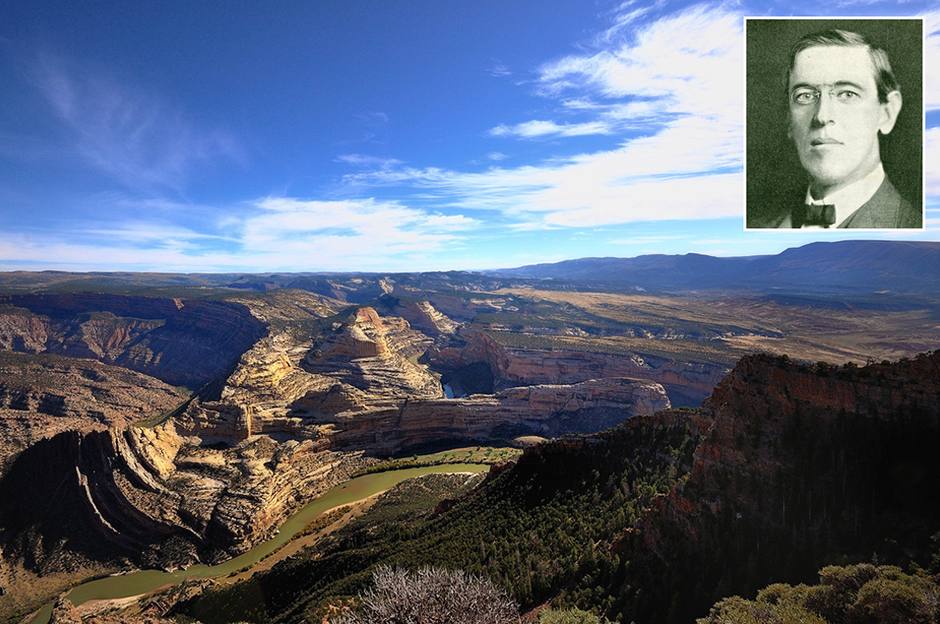

Woodrow Wilson (1913-1921)

Photo credit: Dinosaur National Monument - Mark Stevens, flickr; Wilson - Political Graveyard/Portrait and Biographical Album of Washtenaw County, Michigan, 1891, flickr

Not typically listed among the conservationist presidents, perhaps owing partly to his role signing the infamous bill to dam the Hetch Hetchy Valley, Wilson was a significant wilderness figure nonetheless. He designated more national monuments than all but three other presidents, including the iconic Dinosaur National Monument between Utah and Colorado. Additionally, Wilson signed into law the act that created the National Park Service in 1916, allowing management of current and future parks and monuments.

Wilson’s administration also created numerous new national forests and presided over the creation of several new national parks, including icons like Grand Canyon National Park (formerly a forest reserve and national monument), Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park and Alaska’s Mount McKinley National Park (the first ever in that state).