10 parks and monuments to celebrate Juneteenth

Brick Baptist Church at Reconstruction Era National Historical Park, South Carolina

NPS

Historic sites chronicle Black perseverance

Juneteenth is an annual celebration held on June 19 that marks the anniversary of the end of slavery in the U.S. On that date in 1865, Union troops arrived in Galveston Bay, Texas, carrying news that the Civil War was won and the Emancipation Proclamation was in effect. Though the proclamation had actually been issued two years earlier, slavery persisted—along with fighting between Union and Confederate forces—in many areas, especially west of the Mississippi River. The Juneteenth announcement meant that hundreds of thousands of enslaved Black people in Texas were now free.

Though slavery in the U.S. wasn’t actually eliminated until the ratification of the 13th Amendment later that year, Juneteenth soon became a joyous and hallowed day in Black communities. In recent years, the holiday has gained broader recognition. It’s the nation’s second Independence Day, an opportunity to tell the stories of enslaved and formerly enslaved Black people and reflect on Black resistance and perseverance.

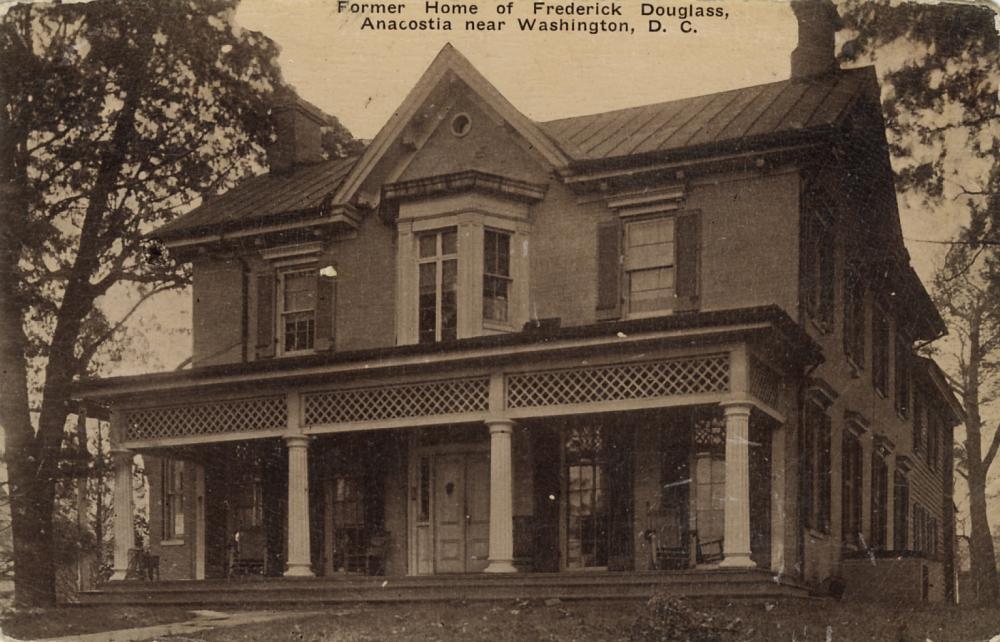

Early 20th century photo of Frederick Douglass' Cedar Hill estate. now site of the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, Washington DC

StreetsofWashington, Flickr

Below, we’re looking at a few extraordinary parks, monuments and outdoors spaces that are suited to that purpose. These spots not only recount history in stirring fashion, but serve to underscore that the work of liberation and racial equity is ongoing.

As you’re browsing this list, keep in mind that the work of ensuring public lands are representative of the nation’s diversity is ongoing, too. Though progress has been made in recent years, there are still comparatively few monuments and other sites dedicated to women, people of color and LGBTQ+ people. In addition to telling more complete stories about our history, rectifying that imbalance will help make the outdoors more inclusive and welcoming for all.

Marshland at Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park, Maryland

NPS

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park (Maryland)

The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument was designated by President Obama in 2013 to celebrate the great abolitionist and national hero known as “Moses of her People" (it's now called Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument and National Historical Park). Tubman overcame cruel abuse and slavery herself to become the most famous “conductor” on the Underground Railroad, leading dozens of enslaved Black people to their freedom (as Tubman noted, “I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger”).

Neighboring the monument on Maryland's Eastern Shore is Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge. Now a bird sanctuary, this land was where Tubman learned vital outdoor skills while navigating Blackwater’s Stewart's Canal, which was dug for commercial transportation between 1810 and 1832 by enslaved and free people.

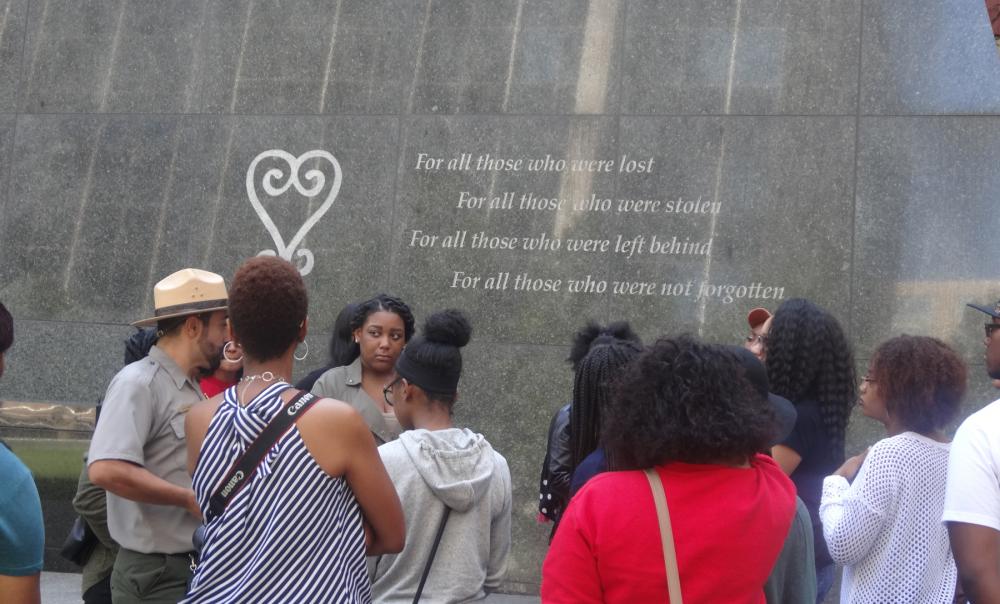

Freshman class students from Howard University stand near engraving of the Ghanaian "Sankofa" symbol and at the African Burial Ground National Monument, New York

NPS

African Burial Ground National Monument (New York)

As its name suggests, African Burial Ground National Monument is a site both solemn and momentous. In 1991, what began as construction in lower Manhattan yielded one of the most important archaeological finds of recent times: a burial ground containing the remains of hundreds of free and enslaved Africans buried in the late 17th through 18th centuries, plus hundreds of artifacts. The monument is considered the first large-scale physical vestige of Black life in the region. Today a wall of remembrance honors those who once used this place to maintain and celebrate their ancestral heritage.

Brick Baptist Church at Reconstruction Era National Historical Park, South Carolina

NPS

Reconstruction Era National Historical Park (South Carolina)

At the very end of his presidential term, President Obama established this, the first national monument that recognizes the post-Civil War Reconstruction era (Congress later expanded it and re-designated it as a national historical park). Reconstruction was a time of change and upheaval—the U.S.’ “second founding”—and the park ably tells the story of the integration of millions of formerly enslaved Black people into the imperfect fabric of American life. The park includes the site of one of the first schools for freed formerly enslaved people and the Brick Baptist Church, which was built by enslaved people and eventually adopted as their place of worship when the land was otherwise abandoned.

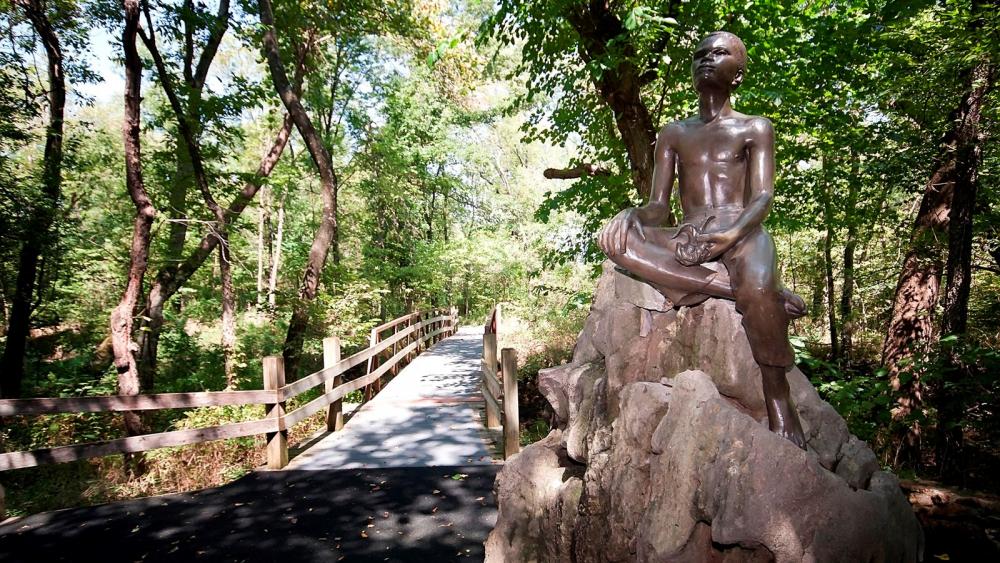

Statue of young George Washington Carver at George Washington Carver National Monument, Missouri

NPS

George Washington Carver National Monument (Missouri)

In 1943, Congress dedicated George Washington Carver’s boyhood home near Diamond, Missouri as a national monument to celebrate his influence on agriculture in the early 19th century, seen in the now-common practice of rotating crops to allow nutrients in the soil to recover. This innovation stemmed from a conservation ethic that was ahead of its time.

Carver was born into slavery and overcame hardship and bigotry—he reportedly showed up for the first day of college classes and was sent away when school officials realized he was Black—to become perhaps the most prominent Black person in America (indeed, one of the most famous people, period). His monument was not only the first to be dedicated to an African American, but also the first dedicated to an American who never served as president.

The historic Robbins House at Walden Pond State Reservation, Massachusetts

Todd Van Hoosear, Flickr

Walden Pond State Reservation (Massachusetts)

Walden Pond is practically synonymous with the writer Henry David Thoreau, and it’s firmly ensconced in the American imagination as a pocket of isolated and otherwise uninhabited nature thanks to his 1854 book “Walden.” However, formerly enslaved Black people lived in Walden Woods years before Thoreau arrived, and even inspired him enough to be mentioned in his manuscript (Zilpah White was a formerly enslaved woman who was able to move out of her household and build her own life, a rare feat; Thoreau recounted her story, including cruel harassment directed at her by white locals). Visitors can learn about Black history and abolitionist activism in the area at the historic Robbins House, which belonged to formerly enslaved Revolutionary War veteran Caesar Robbins.

Divers at Biscayne National Park, Florida

NPS

Biscayne National Park (Florida)

Preservation of this gorgeous marine park was made possible by the Jones family of Porgy Key-- beginning with farmer Israel Lafayette Jones, who was likely born into slavery yet went on to build a multi-generation lime and pineapple empire. It fell to his son, the poetically named Sir Lancelot Garfield Jones, to resist developers and eventually sell the family's land to the National Park Service to be incorporated into the then-new Biscayne National Monument, established by President Lyndon Johnson in 1968. In recent years, Biscayne has played host to a program in which in which predominantly Black divers work with the National Park Service to survey historic shipwrecks, notably the Guerrero, a Spanish slavers’ ship. Unfortunately, the park has been identified by the Department of the Interior as vulnerable to sea-level rise and other climate change effects.

Mammoth Cave National Park, Kentucky

NPS

Mammoth Cave National Park (Kentucky)

Mammoth Cave was once among the United States’ preeminent tourist destinations. And for years, the guides who helped visitors navigate its subterranean twists and turns were enslaved Black people. Those and later generations of guides included figures like Stephen Bishop, Mat Bransford, Nick Bransford, Ed Bishop, Ed Hawkins and Will Garvin, who are now credited with playing a vital role in the development of cave exploration and public tours at the park in the 19th and early 20th centuries. After the end of slavery, when segregation laws still severely limited where Black people could travel and lodge, Mammoth Cave came to host a rare summer resort that catered to African Americans specifically, owned by Mat Bransford’s grandson. Many years later, Mat Bransford’s great-great-grandson became a guide at Mammoth Cave, continuing a family legacy like no other.

Washington Ditch in the Great Dismal Swamp, Virginia

M. Reed, NPS Natural Resources, Flickr

Great Dismal Swamp (Virginia)

Don’t judge it by its name alone. Great Dismal Swamp was actually home and refuge to generations of Indigenous and Black communities, residents of which carved out a vibrant and self-sufficient existence hidden from those who subjugated and enslaved them (As Tom Wilson, who escaped slavery and put down roots in the Great Dismal, memorably said, “I felt safer among the alligators than among white men”). The swamp is home to the largest known collection of archaeological artifacts from Maroon colonies (generational communities of Black people who escaped a slaving society by living hidden in the marshes) and a thriving community descending from early colonial Free People of Color whose families resisted oppression by retreating toward the edge of the swamp.

Currently, there is an effort to designate a national heritage area in and around the Great Dismal Swamp. As members of the community-led Great Dismal Swamp Stakeholder Collaborative, we work to advance legislation like this, which will protect both the natural and cultural heritage of the swamp.

Nathan and Mary “Polly” Johnson House at New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park, Massachusetts

Daniel Case, Wikimedia Commons via GPA Photo Archives, Flickr

New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park (Massachusetts)

This park is devoted to the 19th century whaling boom in the region, but it’s also a good place to look back at what was a renowned stop on the Underground Railroad and a surprising hotbed of abolitionist activism. It was in the New Bedford home of Nathan and Mary “Polly” Johnson, free Black people, where Frederick Douglass first lived after escaping from slavery. The area was also home to Black Civil War hero William H. Carney, Jr., who escaped from slavery with his father as a boy and later became the first Black person to be awarded the Medal of Honor.

Reconstruction of the "Growlery" on the grounds of Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, Washington, DC

Lorie Shaull, Flickr

Frederick Douglass National Historic Site (Washington, DC)

Established in Frederick Douglass’ Cedar Hill estate on the east side of the Anacostia River, this historic site is dedicated to the life and works of the namesake abolitionist, orator and political leader. Douglass escaped from slavery as a young man and became a towering figure in American history, recording his story in among the most important and widely read autobiographies of all time and becoming a forceful advocate for racial equality and women’s suffrage. At the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, visitors can see his personal library and step inside a reconstruction of the solitary “Growlery” he used for some of his deepest thinking and writing.