11 national parks and sites where Black history happened

The Edmund Pettus Bridge over the Alabama River in Selma, Alabama.

Tony Webster, flickr

Sites tell stories of park rangers, the Underground Railroad and jazz music

There are more than 400 National Park Service sites across the country. And while everyone deserves access to their beauty, national parks and other public lands have been a largely white institution. Just 23 percent of visitors to those national parks, and a little under 17 percent of the agency’s full-time workforce, are people of color. Only 6 percent of visitors and 7 percent of staff are Black.

Many experts believe the historic and present-day effects of racism and segregation, and the psychological scars of racial mistreatment in public land settings, are some of the reasons for this lack of diversity. Many Black folks do not feel safe or welcome in national parks. Many Black people also lack equitable access to public transportation or the time and money needed to enjoy public lands and green spaces.

Black people have ensured Black history is preserved and celebrated in many parks across the country—including some you probably haven’t heard of

Needless to say, there is still a lot of work to do in correcting those problems. Part of that work is ensuring parks, monuments and other protected sites are not only equitable in terms of access, but tell a more inclusive and honest variety of stories about our history.

But while Black people and Black history remain underrepresented in parks and monuments, Black people have still managed to ensure that Black history is made and preserved in many national parks across the country—including some you probably haven’t heard of.

Here are a few National Park Service sites that tell some of the lesser-known stories of Black communities and culture in the United States.

Nicodemus National Historic Site, Kansas

The Nicodemus National Historic Site preserves the remnants of a town in Kansas that was founded by formerly enslaved Black people during the period of Reconstruction after the Civil War. Nicodemus was the first free Black community west of the Mississippi River and is the oldest and only remaining Black settlement west of the Mississippi River today. It is a living history lesson on Black survival in America.

District #1 Schoolhouse at Nicodemus National Historic Site, Kansas.

Will Pope, NPS

Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site, Alabama

Before 1940, Black people were barred from flying for the U.S. military. Pressure from civil rights organizations led to the formation of an all-Black fighter squadron based in Tuskegee, Alabama. Starting in 1941, about a thousand Black pilots were trained at Tuskegee for five years. Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site is the training site of that squadron of the first-ever Black military pilots, known as the Red Tails.

P-51 Mustang in museum at Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site, Alabama.

Adam Jones, Flickr

Stonewall National Monument, New York

The Stonewall National Monument commemorates an important site and event in LGBTQ history: the Stonewall Uprising. Stonewall Inn was popular with the Black and Latinx LGBTQ communities, and the crowd in the early hours of the June 28, 1969 uprising included many people of color. A prominent figure in the uprising was Marsha P. Johnson, an activist and self-identified drag queen, who continued to be a major player in the LGBTQ rights movement during the 70s and 80s.

A statue of Marsha P. Johnson stands in Christopher Park, in front of the Stonewall Inn, in 2021. It has since been moved to New York City’s Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center

Elvert Barnes, Flickr

Boston African American National Historic Site, Massachusetts

The free Black community in Boston provided support and a welcome sanctuary for many people escaping slavery on the Underground Railroad. In fact, they played an integral role in the fight to abolish slavery. Along the Black Heritage Trail, within the Boston African American National Historic Site, you will find homes, schools and churches. Those include the African Meeting House, which served as a spiritual, cultural and political center, and the Abiel Smith School, the first schoolhouse in the nation built for the sole purpose of educating Black students.

Exterior of the African Meeting House in Boston, Massachusetts.

NPS

Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail, Alabama

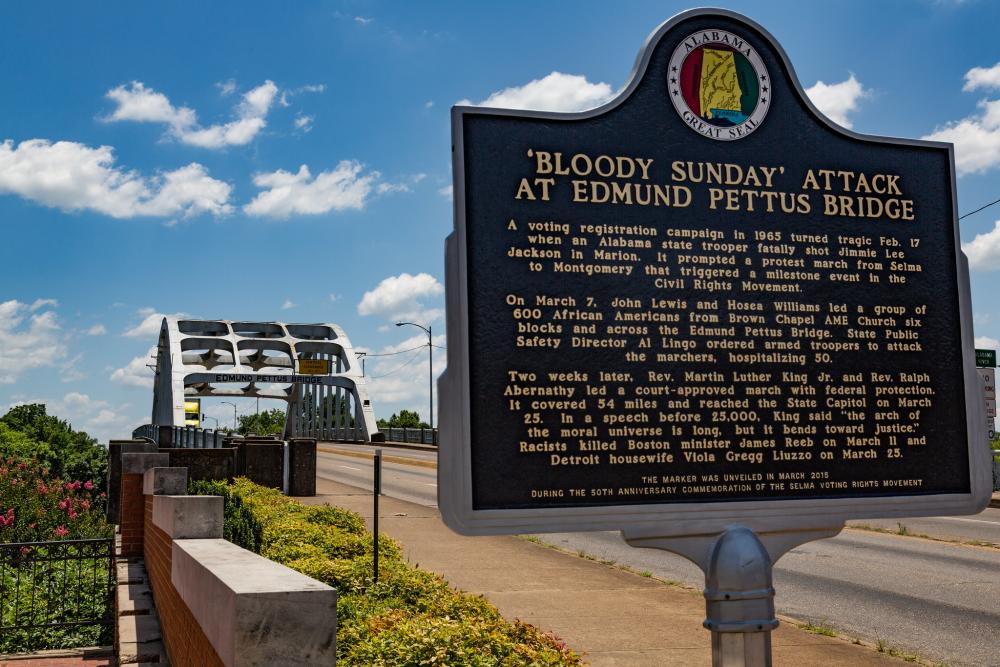

The Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail commemorates and honors the 1965 civil rights marches. On March 7, 1965, the first leg of the march began as a group of more than 600 voting rights advocates crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Nonviolent marchers were met by white supremacist law enforcement and were brutally beaten in what became known as Bloody Sunday, footage of which shocked many people around the U.S. Outrage swept the country, with sympathizers traveling across the country to join the march, which was resumed on March 21, this time with a court order and state and federal law enforcement protection. Four days later, the march reached Montgomery, with the crowd growing to 25,000. These events are considered to have helped spur the passage of the Voting Rights Act later that month.

A historic marker at the Edmund Pettus Bridge, part of the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail, Alabama

Tony Webster, Flickr

Pullman National Historical Park, Illinois

The Pullman porters were indispensable to the success of the passenger railroad industry. Starting in the 1860s, and for decades to come, the Pullman Company hired Black men, known as Pullman porters, to serve first-class passengers traveling in the company’s sleeping cars. The 1894 Pullman strike, and the subsequent national boycott of Pullman train cars, led to the establishment of Labor Day. Later in 1925, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was founded, which is thought to have been the first-ever African-American labor union. These stories are preserved at the Pullman National Historical Park.

Clock tower at the Pullman National Historical Park in Illinois.

Daniel Pels, NPS

Yosemite National Park, California

An early example of Black people playing a critical role in protecting and building the infrastructure of national parks was the Buffalo Soldiers, Black regiments formed after the Civil War. Buffalo Soldiers helped protect Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks from threats like wildlife poaching and illegal logging; putting out forest fires; and even building roads and trails, many of which are still in use today. They also served as rangers in Hawaii and Glacier National Parks.

The legacy of the Buffalo Soldiers is tainted by their role in the U.S. Army’s killing and displacement of Indigenous peoples—but this, too, is an important part of history to be remembered and reflected on.

Potter Point, Amelia Earhart Peak at Yosemite National Park in California.

Steve Dunleavy, Flickr

New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park, Louisiana

Jazz is largely considered by music historians to have originated from Black musicians in New Orleans. Due to its unique blend of cultures, jazz emerged as a fusion of ragtime, blues, traditional African and Caribbean rhythms, black spirituals and a dash of European influence. Jazz music also played a critical role in the Civil Rights Movement. The New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park provides venues and other opportunities for people to experience jazz music and culture in the city.

All Around Brass Band play at New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park in Louisiana.

NPS

Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site, Arkansas

In 1954 the Supreme Court ruled that segregated schools were illegal in the Brown v. Board of Education decision. In 1957, Little Rock Central High School became a flashpoint in the civil rights movement as white supremacists resisted efforts to integrate when the “Little Rock Nine” enrolled at the school. The nine Black teens, who had entered the school under federal troop escort, were harassed by white students every day. On May 27, 1958, Ernest Green became the first Black student to graduate from Central High.

The main entrance of Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site.

NPS

Lincoln Memorial, Washington, DC

The Lincoln Memorial is an important symbol of the civil rights movement. On Easter Sunday 1939, legendary opera singer Marian Anderson sang there in front of 75,000 people after she was refused a performance at Washington’s Constitution Hall by the Daughters of the American Revolution, because she was Black. Years later, in 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech from the memorial's steps to more than 250,000 participants in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

An aerial view of the marble Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC.

U.S. Park Police

Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley National Monument, Illinois and Mississippi

On July 25, 2023, President Biden designated Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley National Monument to preserve a crucial and powerful part of America’s civil rights history. In 1955, Emmett Till was just a 14-year-old Black boy when he was accused of flirting with a white woman and brutally murdered by two white men. The killers, Roy Bryant and his half-brother J.W. Milam, were found not guilty by an all-white jury. Decades later, in 2017, the woman recanted her testimony.

The Monument will span three sites in Illinois & Mississippi. They include the Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ in Chicago, where Till’s funeral was held; the Graball Landing in Tallahatchie County, Mississippi, where locals believe Till’s body was pulled from the Tallahatchie River; and the Tallahatchie County Second District Courthouse in Sumner, also in Mississippi, where Till’s killers were acquitted.

The Tallahatchie County Courthouse in Sumner, Mississippi.

NPCA