Extreme weather is battering national parks, forests and other public lands

Dried mud at Joshua Tree National Park by Brad Sutton, NPS; Hurricane Sandy storm damage at Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge by USFWS, Flickr; Las Conchas Fire by Jayson Coil, Flickr; Sun by Johan Elder, Flickr

Climate change-fueled fire, drought, storms hurt ability to adapt

This blog post is part of a series on extreme weather. Click here to read about the historic drought impacting the West and how public lands can help.

-

WILDFIRE - Santa Fe National Forest (New Mexico), Bandelier National Monument (New Mexico), Valles Caldera National Preserve (New Mexico), Mesa Verde National Park (Colorado)

-

HEAT WAVES - Saguaro National Park (Arizona), Yellowstone National Park (Montana/Wyoming)

-

DROUGHT - Angeles National Forest (California), Joshua Tree National Park (California), Lake Mead National Recreation Area (Arizona/Nevada), Zion National Park (Utah)

-

STORMS AND FLOODING - Everglades National Park (Florida), national wildlife refuges, Mt. Rainier National Park (Washington)

Smoke from the Las Conchas Fire in 2011

Vic Brown, Flickr

WILDFIRE

At another time, in another place, it might not even have made the local news.

But June 26, 2011, was a dry, windy Sunday in New Mexico’s drought-parched Jemez Mountains—perfect fire conditions. So when a lone aspen fell on some power lines around 1 pm, it instead triggered an unprecedented tragedy.

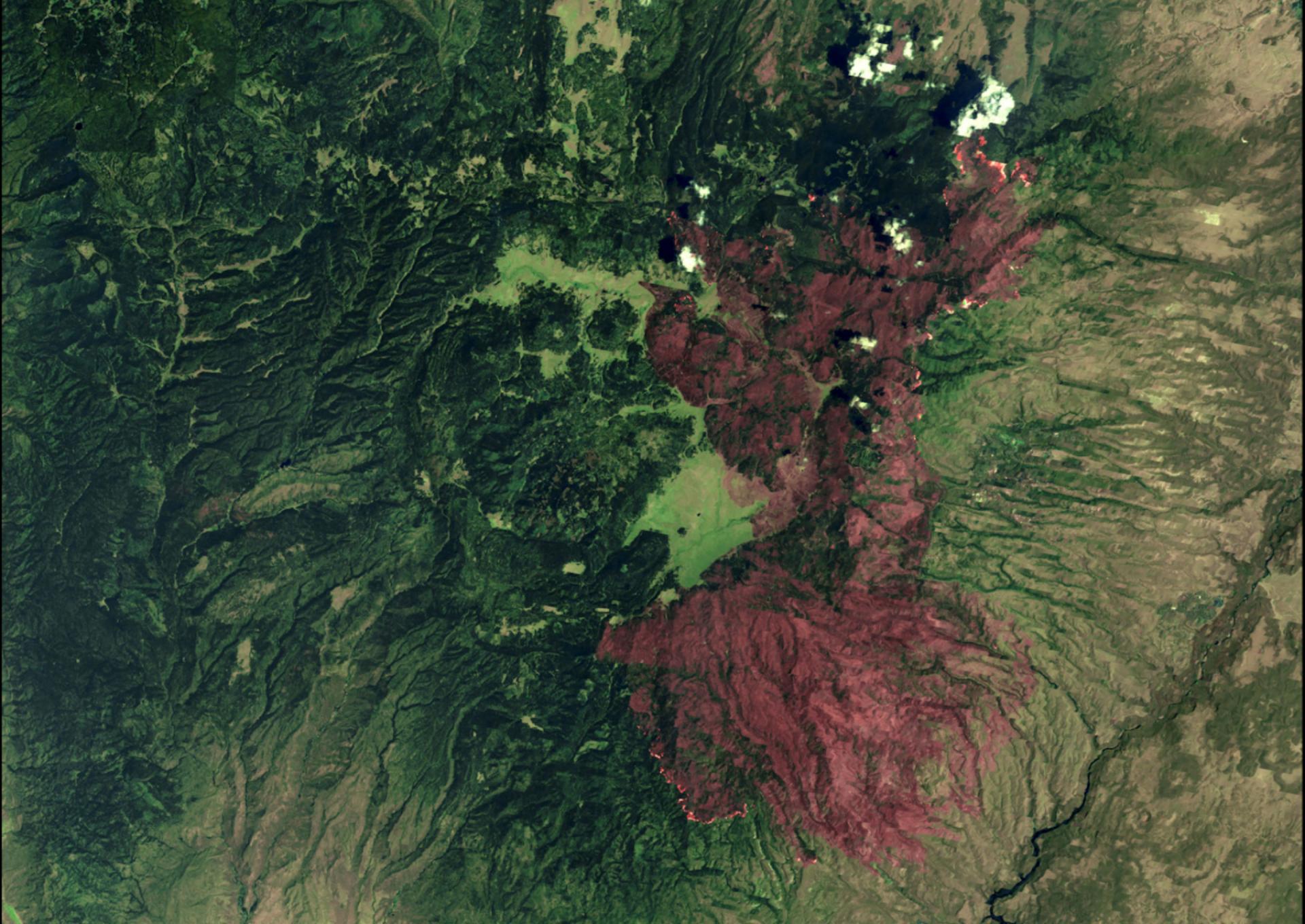

All it took was a few sparks. In the first 14 hours of its life, the Las Conchas Fire burned an acre of forest every 1.17 seconds. A research ecologist working at Bandelier National Monument compared the sight of its ultra-hot “convection columns” raging through ponderosa pine to exploding atom bombs. At night, its apocalyptic glow was clearly visible from Santa Fe, 20-odd miles east of that first ignition. In all, the blaze would eat through an expanse roughly twice the area of Manhattan, destroy more than 100 homes and other buildings and transform a stretch of cool conifer forest into a charred landscape some government scientists later came to call “the heart of darkness.”

The Las Conchas Fire, which started off burning an acre of forest every 1.17 seconds, is illustrative of extreme-weather disasters being fueled by climate change.

The causes of a wildfire are many—and in fact, fire is a natural and healthy part of any forest’s lifecycle. But the Las Conchas Fire is illustrative of extreme-weather disasters that are increasingly being fueled by climate change.

Enabled in part by faulty forest management practices, Las Conchas defied the old “rules” of how fires work. Instead of a small, periodic, basically self-regulating blaze—the kind that happen under a normal fire regime—it fed on unusually severe heat and dryness and emerged a steroid-juiced monster. The fire soon became a data point in research linking more frequent and more destructive big fires to human-caused climate change; a 2014 study looking at it and similar large fires in the western U.S. found that the likelihood that the increasing number of fires and areas burned being “random” was less than 1%.

Cycle of destruction affects public lands and waters

The damage caused by the Las Conchas Fire didn’t stop once the flames finally died down, either. Since the fire scourged plant growth from hillsides, the landscape’s capacity to absorb water and stave off erosion was critically diminished. A summer monsoon soon swept through, causing dangerous flash flooding where there might ordinarily have been only a trivial accumulation of rainwater. And of course, trees destroyed in wildfires release the carbon dioxide they had absorbed and stockpiled throughout life. That means more greenhouse gases in the atmosphere to perpetuate the climate crisis that fuels massive fires like the Las Conchas Fire in the first place.

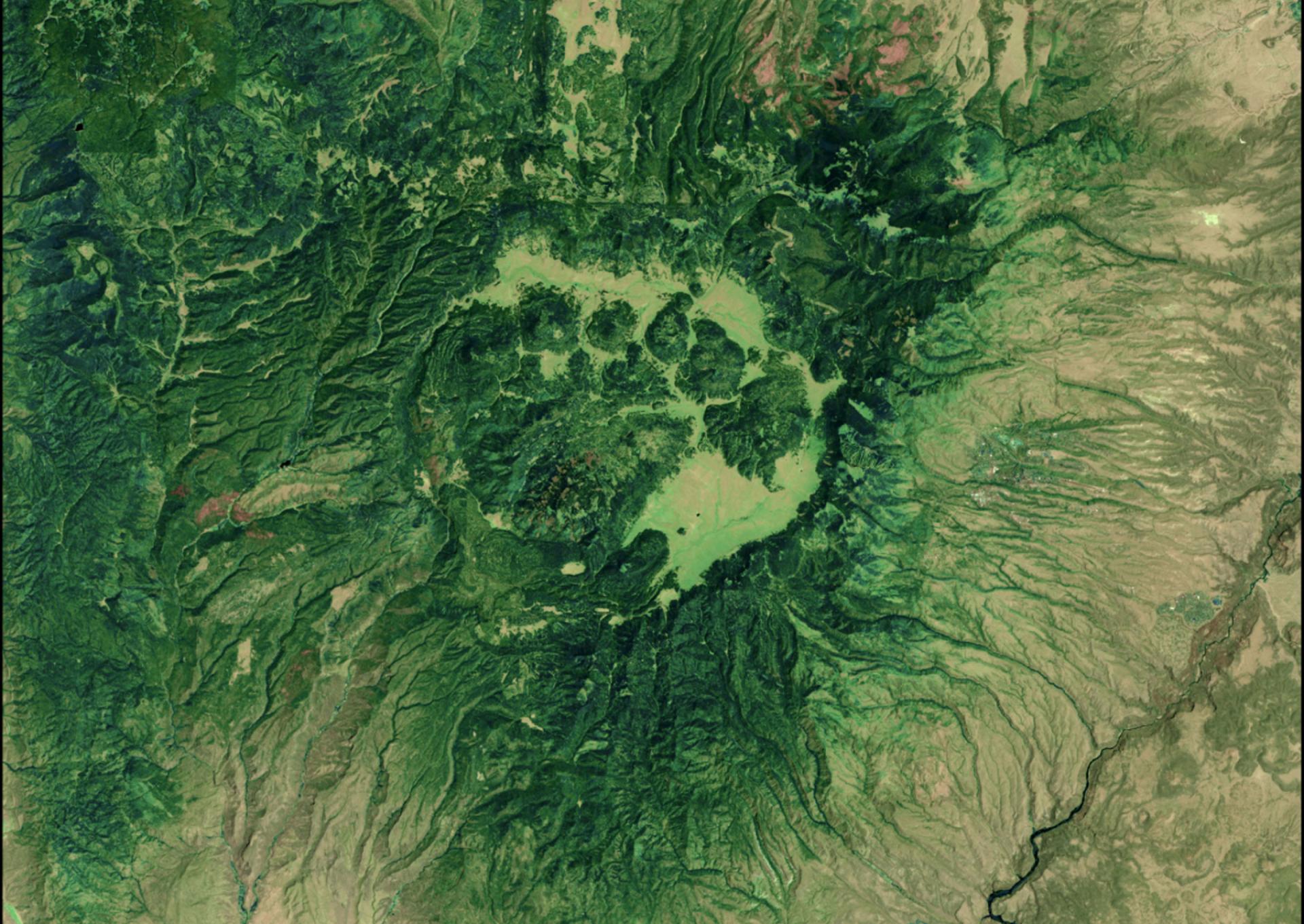

Disasters like Las Conchas hurt not only people and wildlife but the lands and waters that are so vital to our way of life. In this case, the fire ran through parts of Santa Fe National Forest, Bandelier National Monument and Valles Caldera National Preserve, among other lands. The above-mentioned cycle of destruction made trails impassable and left the Indigenous Santa Clara Pueblo community with a badly damaged watershed and infrastructure just to the east.

Illustrating how wildfire can also damage important cultural sites, in Colorado’s Mesa Verde National Park, which records and preserves the history of Ancestral Puebloans in the form of thousands of archaeological sites, fire and fire-fighting activities have damaged or altered ancient carvings.

Aftermath of the Las Conchas Fire in the Jemez Mountains

Paul Asman and Jill Lenoble, Flickr

Such damage strikes at places that can and must help us adapt to, and mitigate, the effects of climate change. Interconnected parks and other lands offer refuge for people and wildlife struggling with extreme heat. Wildlands help to combat climate change itself, as forests and other landscapes absorb and store carbon pollution that is heating up the planet.

As we take stock of extreme weather events and prioritize solutions to address climate change—including rapidly phasing out fossil fuel development on public lands—it's also worth considering how these heat waves, droughts, fires and storms are impacting shared natural and cultural sites. We need every tool at our disposal in good working order if we’re going to confront this existential crisis.

And we’d better do the work fast. In 2012, a wildfire in the Gila National Forest in southern New Mexico broke the Las Conchas Fire's short-lived state record for acreage burned by nearly two-fold, only one year later. Bottom line: These disasters are bad and getting worse. The time to act is now.

A namesake saguaro cactus stands in Saguaro National Park, Arizona

Omar Bárcena, Flickr

HEAT WAVES

One of the best-known examples of climate change-driven extreme heat transforming an iconic public land is in Arizona’s Saguaro National Park. Since the early 1990s, an extended period of extreme heat and drought—especially high nighttime temperatures—has hurt the ability of saguaro cactus seedlings to thrive. This is impacting other flora and fauna in the area and affecting the ability of the Indigenous Tohono O’odham Nation, which already faces many challenges in a rapidly warming region, to continue gathering saguaro for food and other uses.

Recent maximum summer temperatures in the Greater Yellowstone area are hotter than any in the last 1,250 years

Extreme-heat impacts are not limited to the Southwest. Findings published in 2021 reflect that recent maximum summer temperatures in the Greater Yellowstone area are hotter than any in the last 1,250 years. The cascading effects of this warming are numerous. In 2007, a heat wave affecting Yellowstone National Park made a river hot enough to kill hundreds of trout, the largest such mortality event in the long history of the park. Scientists have noted that mountain pine beetles, whose proliferation has been enabled by warmer temperatures, have taken a heavy toll on Yellowstone’s whitebark pine trees. This trend has already altered the ecosystem in fairly dramatic ways, including potentially putting newly meat-keen grizzlies on the path to more frequent clashes with people.

Dry, cracked earth in the Turkey Flats section of Joshua Tree National Park, California

Brad Sutton, NPS

DROUGHT

Extended water shortages manifest on public lands in numerous ways. Recent satellite images succinctly illustrate the before-and-after effects of dry conditions on California’s Angeles National Forest and San Gabriel Reservoir, which have gone from green and blue to brown and gray, respectively. The forest is an important refuge and recreation area for people from Los Angeles County, and the reservoir provides water to communities in the San Gabriel Valley. Both functions are now diminished. Drought has also increased fire risk in the area.

To the east, Joshua Tree National Park has become one of the most recognizable canaries in the public lands coal mine, with young namesake trees and their underdeveloped roots struggling to survive through longer and more frequent droughts. This trend is expected to reverberate through the entire ecosystem. Another western public-lands icon, the Colorado River-fed Lake Mead, has also endured deep drought wounds. A source of water for millions of people and millions of acres of farmland, the reservoir is now marked by a dramatic calcium-deposit “bathtub ring” that shows how far the water level has dropped.

A source of water for millions of people, the namesake reservoir at Lake Mead National Recreation Area is now marked by a dramatic calcium-deposit “bathtub ring” that shows how far the water level has dropped

Drought affects public lands and the people and wildlife that depend on them in less obvious ways, too. Experts now worry the Virgin River, which runs through Utah’s Zion National Park, has become an ideal breeding ground for deadly bacteria and toxins. This has happened in part because the area isn’t getting enough rain, which would ordinarily help dilute and “scour” the waterway.

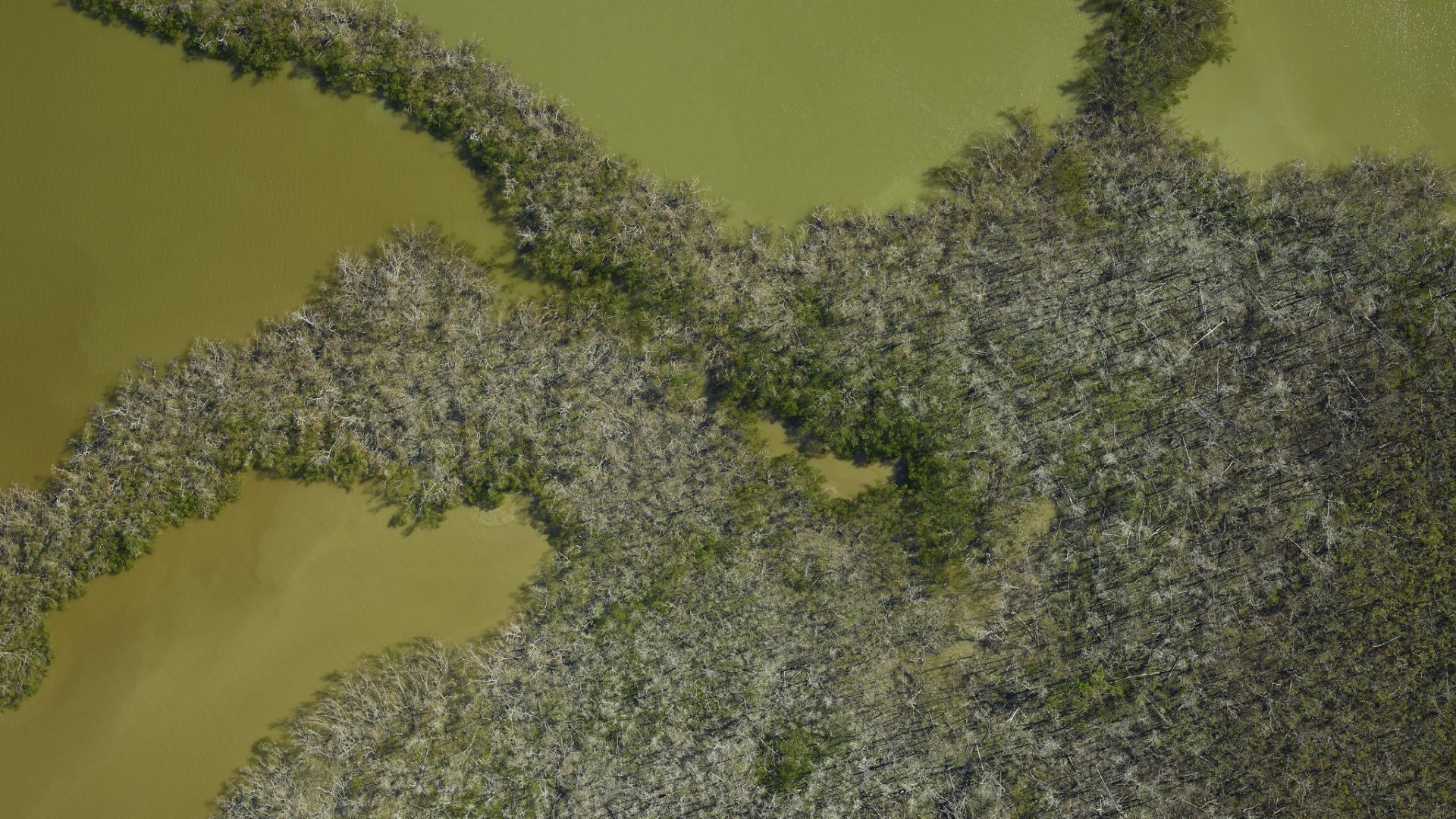

Aftermath of 2017's Hurricane Irma at Everglades National Park, Florida

National Park Service Eastern Incident Management Team, Flickr

STORMS AND FLOODING

Coastal public lands are those most directly affected by stronger storms and flooding. Landscapes like salt marshes and mangrove forests are an important buffer against major storms and flooding – working like a natural sponge to dull the impact of ocean swells – but these same places are being weakened by factors like erosion from more frequent storms.

Everglades National Park serves as a stalwart defense system against hurricanes, but it has already sustained significant damage from storms, exposing millions of people to harm

A prime example is Everglades National Park. It serves as a stalwart defense system against hurricanes but has already sustained significant damage from storms, exposing millions of people to harm. Hurricane Sandy famously pummeled dozens of national wildlife refuges on the East Coast in 2012, and research suggests damage from the storm would have been even worse without wetland intervention—but what about when those marshes see even more big, destructive storms in years to come?

Later, in 2015, severe flooding in the Great Plains—which research determined was made more likely by climate change--overwhelmed a number of national wildlife refuges, including Trinity River National Wildlife Refuge, in Texas. There, wildlife was forced to flee to higher ground and flood waters allowed invasive aquatic plants to spread more quickly. At Hagerman National Widlife Refuge, many trees that had recently endured weeks of drought were unable to tolerate the sudden switch to flood conditions, which led to excess water pooling around their roots.

Inland areas can be affected by big storms, too. In November 2006, Mt. Rainier National Park received such heavy rainfall that flooding forced the park to close for six months. The rushing water uprooted trees and triggered landslides, illustrating how a heavy downpour can change the landscape, and therefore alter habitat and climate refugia.