Horror Stories About Mining: Why we shouldn’t fast-track mining on public lands

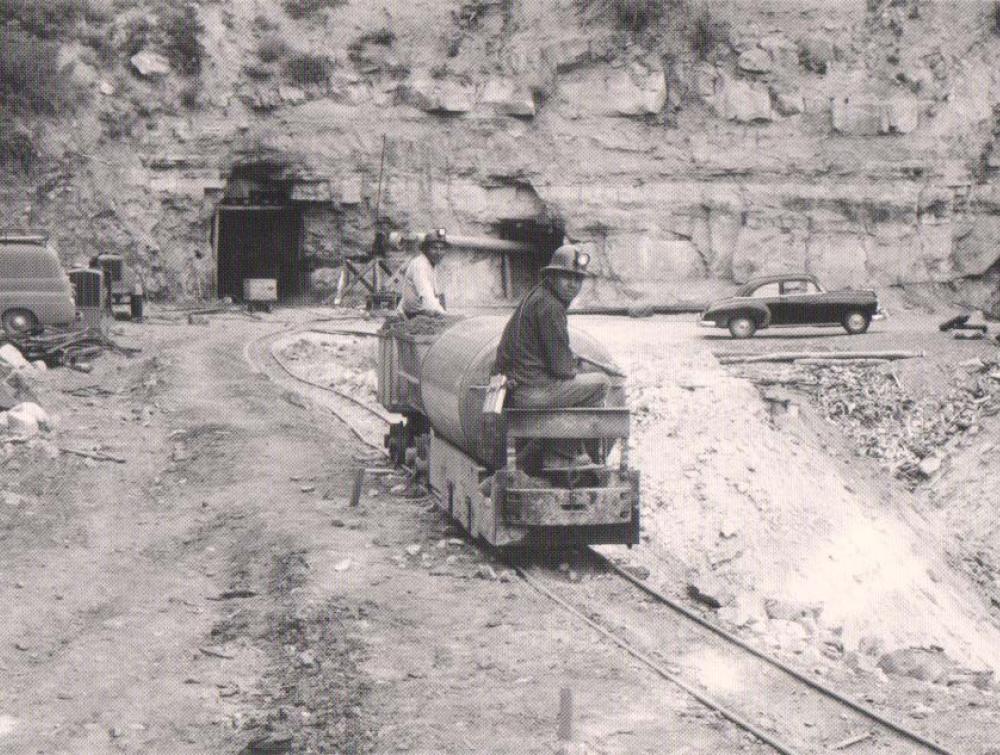

Navajo miners near Cove, Arizona in 1952. Photos originally published n the book "Memories Come to Us in the Wind."

Milton Jack Snow/SERC.CARLETON.EDU/CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Reckless mining is a major threat to human health and the environment

Extracting heavy metals from the Earth is a complex and often dangerous process that can involve blasting rocks, deep drilling and the use of toxic chemicals. If done recklessly, it can leave deep scars in the environment and local communities—and there are plenty of horror stories to prove it.

In spite of those risks, the Trump administration has announced it wants to lift existing bans on new mining claims on public lands. The move could open up the wilderness, areas of critical environmental concern, and even national parks to mining. But that's not all. The government is also considering dangerous measures to fast-track mineral extraction on those lands, including expediting environmental reviews, limiting public participation and encouraging the building of infrastructure to access new mines.

The administration's motivation is to boost production of 35 minerals including uranium, potash, lithium and helium. But if history has taught us anything, is that ramping up mining can do more harm than good. Hardrock mining is one of the most devastating industries to the environment and human health, with impacts that can last for generations.

Instead of loosening protections, we need to increase safeguards for air, land and water so we’re not repeating the mistakes of the past.

Here are two horror stories to remind us about the dangers of increased mineral mining for both humans and the environment:

Communities were contaminated with toxic uranium

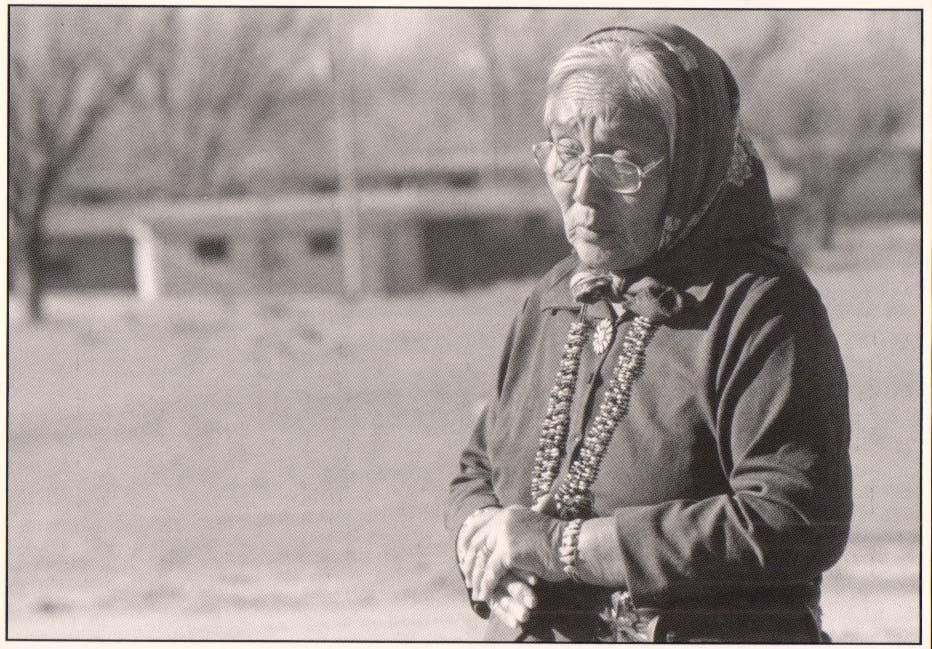

Mary Frank of the Navajo Nation in New Mexico watched her family struggle with health issues that she attributes to nearby uranium mining. Photos originally published in the book "Memories Come to Us in the Wind."

Doug Brugg/SERC.CARLETON.EDU/CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

One of the most harrowing stories of irresponsible mining still haunts a Navajo community to this day. From 1944 to 1986, nearly 30 million tons of uranium ore were extracted in Navajo territories in Utah, New Mexico and Arizona. Uranium was in high demand at the time for use in atomic weapons.

The first sign that something was wrong was a sharp increase in lung cancer among miners. Soon after, families living near extraction sites reported high rates of cancer and kidney disease. Researchers later attributed the illnesses to uranium waste that had leaked from mining sites. Traces of the mineral were found on nearby land, cattle, water wells and even the exterior of houses. Many of those stories were told by Navajo people in the book "Memories Come to Us in the Wind" published in the year 2000.

Navajo communities were eventually able to ban uranium mining and processing on their reservations. But their ordeal is far from over.

More than 500 mines were abandoned by mining companies and continued to release uranium and other metals into the environment. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) vowed to clean up, but the process has been long and costly. In the meantime, medical tests recently conducted by the CDC continue to show high levels of uranium in Navajo peoples, even in babies.

Looking back on Navajo people’s long history with uranium, Navajo Nation Vice President Myron Lizer recently said: “It should come as no surprise, therefore, that the Navajo Nation strongly opposes the permitting of any uranium mining operation near Navajo Nation lands, other tribal lands, and national parks.”

Potash mining has helped to drain the Colorado River

The Moab or Kane Creek potash mine next to the Colorado River

SentinelHub/Fickr/CC BY 2.0

For decades, potash mining in the Colorado River was done the old way — large groups of men would march into deep tunnels by the river’s banks, shovels in hand, to search for the mineral, which is a key ingredient in some fertilizers. But they didn’t always make it out alive. In 1963, an explosion in Utah trapped 25 miners underground, and only seven made it to the surface.

Eventually, potash mining was modernized through technology. But new excavation methods led to other problems — specifically, the enormous amounts of water required in the process. Hot water is pumped deep underground to dissolve chemicals in the ore. The resulting substance is then pushed to the surface where potash is evaporated from massive blue ponds in the middle of the desert.

A lot of the water used in the process comes from the Colorado River, and that is putting a strain on the water flow. “A single potash plant located near the city of Moab in Utah has used around 2,000 gallons of water per minute since it started running in 1964,” said John Weisheit, a local activist and co-founder of the environmental group Living Rivers.

Potash is not the only villain in this story. Population growth, irrigation, and climate change have put the Colorado River in dire straits. Since the year 2000, the river has experienced prolonged drought, and the lower basin has had more demand for water than the river can provide.

Weisheit is concerned that plans to expand potash mining would make matters even worse. In a 2016 report, Living Rivers forecasted that future potash development around the Colorado River would require about 4.6 billion gallons of water per year — three times the amount used by Grand County and San Juan County residents. “There’s just no more water for this in the Colorado River,” he said. “And there are more important uses for the remaining water than potash.”

We need more protection, not less

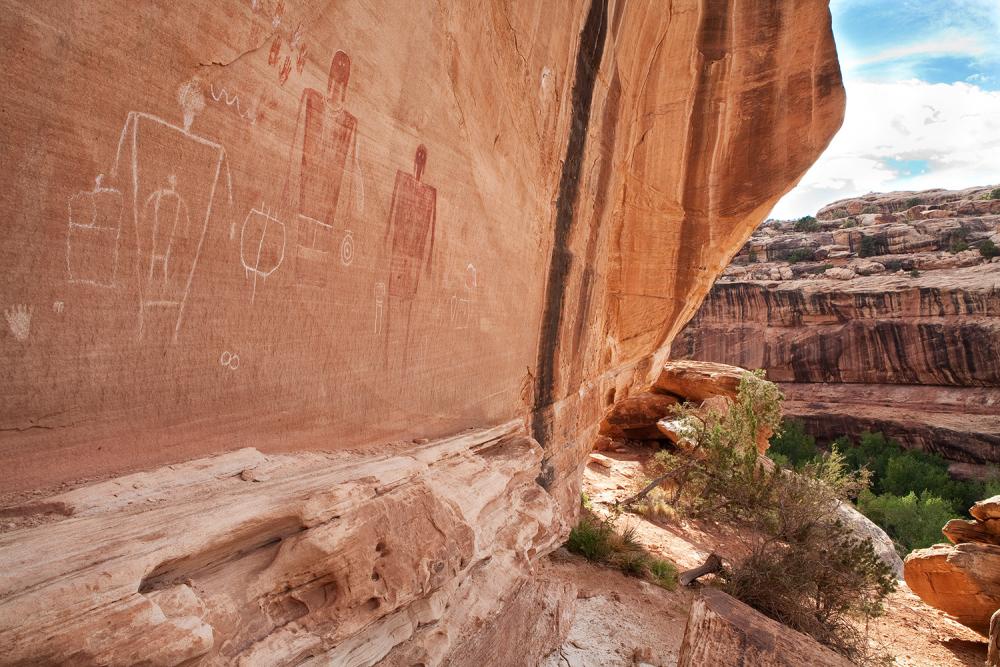

Engravings on a wall at Bears Ears National Monument

Bob Wick/BLM

It might surprise you to learn that the federal law that regulates hardrock mining claims was drafted in the Wild West days. You read that right. The General Mining Act of 1872 was signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant and remains on the books with only minor amendments. The ancient law states that anyone can stake a mining claim on federal law on public lands throughout the country without much scrutiny.

The antiquated system combined with the powerful mining industry has continuously threatened wilderness areas. The most notorious victim so far has been America's beloved Bears Ears National Monument. In 2017, President Trump announced that he would unlawfully gut the monument by 85 percent, eliminating environmental protections on extensive valleys and sandstone cliffs that have tremendous archeological and cultural significance to Native Americans, particularly five tribes of the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition (Navajo, Ute, Hopi, Zuni and Ute Mountain Ute).

Recent media reports revealed the motivation behind the shrinkage was to make the land available for mining. A uranium company with claims in the area met with the Interior Department prior to the cuts (represented by current EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler). And the reduction ultimately benefited the company, by removing protection from land encompassing at least 100 mining claims that they owned.

The gutting of Bears Ears raised alarm bells that another crown jewel could soon be on the chopping block — the greater Grand Canyon. In 2012, one million acres of land surrounding the park was protected with a 20-year ban on uranium and other hardrock mining. But with the government’s latest push to increase domestic production of heavy metals, there’s a risk that protection could be overturned.

Needless to say, we need modern legislation that protects public lands and local communities from the threat of careless mining.

There’s some hope on the horizon. Recently, Representative Raúl M. Grijalva (D-AZ) and Representative Alan Lowenthal (D-CA) introduced legislation that would remove uranium from the administration’s “critical minerals” list. In May 2019, Representative Grijalva and Senator Udall (D-NM) pushed for an update of the country’s antiquated mining law. There are also proposals in the works to protect the greater Grand Canyon watershed and Bears Ears National Monument from new mining. In the meantime, The Wilderness Society and other environmental groups are fighting the illegal reductions of Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante monuments in court.

The Wilderness Society fights mining on the edge of America’s most visited Wilderness area

Erik Fremstad

Starting today, companies can mine in former Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante

Mason Cummings, TWS

Maps: Boundary modifications for Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments

Mason Cummings, TWS