Mohican Sugar Bush Traditions Endure

This November, we are asking our community to reflect on how they have enjoyed the benefits of Native people being removed from their homelands. What are the Native histories of your favorite places outside? Who called that place home before you fell in love with the landscape? How, when and why were Native people removed from that place? How have you benefited from Native erasure?

We understand that these are not easy or comfortable questions to ask ourselves as non-Indigenous people. But during Native American Heritage Month, we believe these are the right questions to ask.

For some Indigenous people, Native American Heritage Month is a time to celebrate our heritage, communities, families, practices and traditions with each other and others. We must all do better to extend the celebration beyond this month to all year. Yet, in the spirit of celebrating and sharing, I have looked at my own family traditions, the lands on which I practice those traditions, and how they are being impacted by a changing climate. Indigenous communities continue to celebrate long held traditional practices and connections to food and the land passed down from one generation to another. Climate change is affecting these practices in real ways from warming temperatures and unpredictable changes in weather patterns to shorter collection periods and in some cases irreparable damage to landscapes.

I am a Little Shell Chippewa tribal member and direct descendant of Stockbridge-Munsee Community, Band of Mohicans and Menominee Tribes. I was born and raised in Wisconsin and live there today. The history of the Tribal Nations I am affiliated with is vastly different from one another. The Little Shell Tribe fought for federal recognition for over a hundred years. The Menominee Tribe retained a fraction of its ancestral homelands and survived termination and restoration. The Mohican Nation survived upwards of nine removals from the East to today’s present lands which were the ancestral homelands of the Menominee Nation.

Though each of the Tribal Nations has a different history, they all managed to preserve important traditions passed down through ancestors dating thousands of years back. My family’s tradition of making maple syrup at Sugar Bush camp is an important time-honored tradition that endures despite challenges of forced removals, land dispossession, other harmful federal policies meant to eradicate or assimilate Native peoples, and new challenges stemming from the climate crisis.

According to A Brief History of the Mohican Nation Stockbridge-Munsee Band, “In the early spring, the [Mohican] people set up camp in the Sugar Bush. Tapping the trees, gathering the sap, and boiling it to make maple syrup and sugar was a ceremony welcoming Spring,”

Many Indigenous families from the woodland’s region continue this practice and tradition today, including my own family. Every year, the Miller Family gathers on the Stockbridge-Munsee Reservation near Bowler, Wisconsin in early Spring to set up camp in the Sugar Bush. Our Sugar Bush is located on reservation trust land amidst a bush of maple sugar trees referred to as a “Sugar Bush.” We lay our tobacco down with a prayer to our Maple Sugar Tree relatives and give thanks, tap the trees, gather the sap, and boil it to make maple syrup as a welcoming ceremony to Spring—like our ancestors have done for thousands of years.

We spend quality time together outdoors with all ages and relatives in this ceremony. This traditional practice might be modernized in some ways like the metal taps and plastic bags we use but the core practices have stayed the same. Reconnecting with all relatives, asking for permission to take, giving thanks, family, spring, fire, food, stories, and collective work. It includes our immediate family, grandparents, aunts and uncles, nieces and nephews, community members, visiting friends, and everyone’s dogs.

Every person contributes to the event. They might cook, gather, cut, and stack firewood, put sap bags together, lay hay and pallets down to quell the mud, drill holes for taps, hang sap bags, keep fire, empty bags of sap into collective catchment, boil sap, share stories, food, and music. After boiling for many hours over an open fire, we later work together as a family to finish the syrup by straining through very fine mesh to rid it of small bits of debris and then bottle and store it for family use. Spending time together and passing on traditions, stories, and knowledge is important. The food source we collect and use as a family is well loved. The time outside is a refreshing break from home hibernation of the winter. Some springs are colder than others—but we brave through it together. The process is filled with collective decisions and actions.

Below please find a pictorial story of the some of the collective processes we endeavor as a family carrying on Sugar Bush traditions.

Here, the Miller Family works together to prepare the sap collection bags a few weeks before Sugar Bush time.

In sap camp, everyone has a job. Moss Campbell Miller (3), Mohican tribal member, loads the finished sap collection bags in a sled for hanging on taps later.

My husband, Beau Miller, a Mohican tribal member and Tribal Conservation Officer for the Stockbridge-Munsee Community, places metal taps in Maple Sugar trees.

Beau teaches his son, Miles Aupaumut Miller, also a Mohican tribal member, how to use a stick to clear the drilled hole of debris for the tap.

Gregory Miller, Mohican tribal member and my father-in-law, shows his grandson, Corlyss Moderson, how to set the tap and bag.

Miles Aupaumut Miller checks the Sugar Bush and how full the sap bags are after they have been set.

Leslyn Lucille Welch and Miles Aupaumut Miller, cousins, work together to collect the sap from collection bags and pour it into pails for transfer to the sap pan.

On a bright sunny day, Beau Miller hauls sap out of the Sugar Bush.

The Miller family walks out of the Sugar Bush after collecting the sap from bags, into pails, and then into the catchment system pulled by a UTV.

Pails of sap wait to be poured into the sap pan. We hand harvest and boil over an open fire to get the syrup. While it takes longer, the practice of this tradition is strong.

Family and friends of all ages boil the sap in the big sap pan.

Meryl Blue Miller, Mohican tribal member, enjoys a warm sunny spring day while sap boils behind in the sap pan. Each year, the weather is different. The best sap season consists of cold nights and warm days.

Uncle Don Miller skims the sap pan for foam. He has since passed on but the traditions he taught the Miller Family children continue to live on.

Here, Miles Aupaumut Miller, carries on a tradition he learned from his Uncle Don and others as he skims the sap pan for foam.

The Miller Family measures the sugar content of the sap which is finally turning into syrup.

Pictured here, the Miller brothers, Trace and Beau. Boiling sap takes long hours of tending to the fire and sap pan. Sharing food and stories is essential.

A tent set up in Miller Sugar Bush camp glows brightly.

The sap is now syrup. Family works to quickly transfer into waiting milk cans for later finishing and bottling.

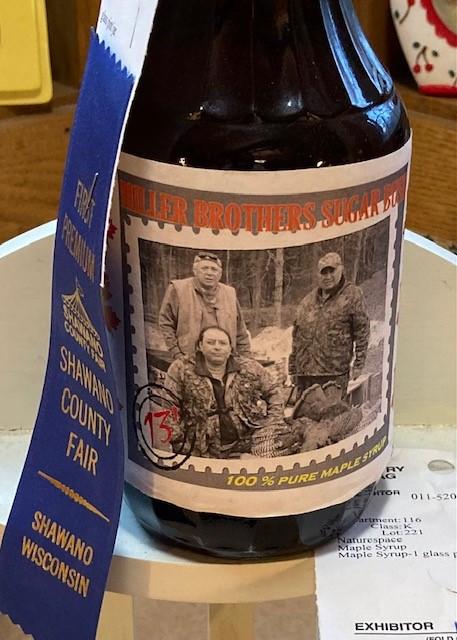

A bottle of finished syrup features the Miller Brothers, Don, Greg, and Bud. It routinely wins blue ribbons from the Shawano County Fair when submitted.

“Because the tapping season is dependent on weather conditions, maple syrup production is particularly vulnerable to changes in climate,” according to the U.S. Geological Survey and research from the Climate Adaption Science Centers. “Warming temperatures, changes in precipitation, and changes in freeze and thaw cycles will impact maple trees and syrup production...Maple syrup is also a traditional food source for a number of tribes in the region, such as the Menominee Tribe.”

During the Covid19 pandemic before vaccines, family gatherings for syrup production decreased and, in some cases, did not occur due to fear of harm to gathering families. These global threats have real impact on Indigenous families and the passing down of traditional knowledge and everyday practice. In 2021, the Miller sap camp was smaller due to the Covid19 pandemic. In 2022, the Miller sap camp was back to its large family size.

However, on June 18th of 2022, an EF-1 tornado with winds of approximately 86-110mph blew through the Stockbridge-Munsee Reservation and the Miller Sugar Bush suffered severe damage. As a result, we lost many older Maple Sugar relatives and held a prayer service as a community to memorialize their spirits and process our grief at the Church of the Wilderness. Today, the Sugar Bush we have loved and celebrated each Spring with for generations is a graveyard of great relatives now resting, only stumps to mark where they once stood.

Here is what the Miller Sugar Bush sap pan area looks like today after an EF-1 tornado blew through the Stockbridge-Munsee Reservation on June 18, 2022.

This is the Sugar Bush area where approximately 90 Maple Sugar tree relatives once stood.

Stumps in the Sugar Bush after some logs were salvaged by the Tribe’s Forestry Department.

Although it is hard to see the scale of destruction from the EF-1 tornado, this picture depicts some of the destruction of the Sugar Bush.

The Miller Family will continue to process our grief over this loss of relatives and the landscape and take comfort in gathering and making decisions about the future of our Sugar Bush traditions and its location in 2023. We may have to move on to a different location, we may have to harvest less but the traditions of holding a Miller Sugar Bush camp will endure as they have for generations before.

Many people globally are facing similar realities of adapting to a warming climate and experiencing more frequent severe weather events. Ensuring that our ways of life and the traditions we hold close are passed on to future generations requires collective action. Listening to communities most impacted by the climate crisis, advocating for change, pressuring decisions makers to do better, and thinking globally and acting locally – such as we do in the Sugar Bush – is what will make the difference.