By the numbers: Why this ancient rainforest is an important climate solution

Tongass National Forest, Alaska

Colin Arisman

Alaska’s Tongass absorbs more carbon than all other national forests

Trees absorb carbon dioxide and give off oxygen. This makes them some of our greatest allies in the fight against the climate crisis.

Big, dense, old-growth forests are especially good at absorbing and trapping (or “sequestering”) carbon, the leading greenhouse gas causing climate change. The Tongass National Forest in Alaska is often referred to as “America’s Climate Forest,” the nation’s “climate insurance policy” and “a national champion” of carbon sequestration.

But that only works if they're left standing. Once cut down, these trees release their stored carbon and can exacerbate the climate crisis. That’s why we need to protect old-growth trees in places like the Tongass.

The Trump administration got rid of protections for the wildest parts of the Tongass. The White House said it plans to review that decision. We encourage President Biden to follow through on that promise and ultimately restore protections to this ancient rainforest.

Tongass National Forest, Alaska

TWS

Let’s take a look at some key facts about why forests—and specifically the Tongass National Forest—are an important climate solution.

Tongass National Forest has been called a “key weapon" for fighting climate change. The reason: big, old-growth trees are highly effective at trapping climate-warming greenhouse gas like carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing (or “sequestering”) it. Scientists have estimated that the Tongass accounts for about 8% of the carbon sequestered by all national forests.

Bottom line: if left standing, these trees are crucial to combating the climate crisis. But when old-growth trees are logged, they release carbon back into the atmosphere, exacerbating the climate crisis rather than helping it. Research has found that carbon density in unmanaged forests is 60% higher than in managed forests. In other words, forests like the Tongass are most effective in helping the climate crisis when left alone.

Scientists have known for quite some time that plants—especially trees—are big-time absorbers of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. A 2011 study tried to quantify the worldwide effect and reported a net global forest sink of as much as 1.1 petagrams—1.1 billion metric tons—of carbon per year. According to the EPA’s calculator, that means the world’s forests annually remove carbon from the atmosphere equivalent to that contained in nearly 54 million tanker trucks’ worth of gasoline.

Tongass National Forest, Alaska

Colin Arisman

In recent weeks, the Biden administration has been emphasizing the importance of “nature-based solutions” as part of plans to address climate change. An oft-cited 2017 article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that such tools, including preventing the loss of forests, could account for more than one-third of carbon-mitigation needed to limit climate change to 2 degrees by the year 2030. Of those natural climate solutions, over two-thirds were related to forests (including management changes, planting new forests, etc). The report concluded such methods "will be a large component of any successful effort to mitigate climate change."

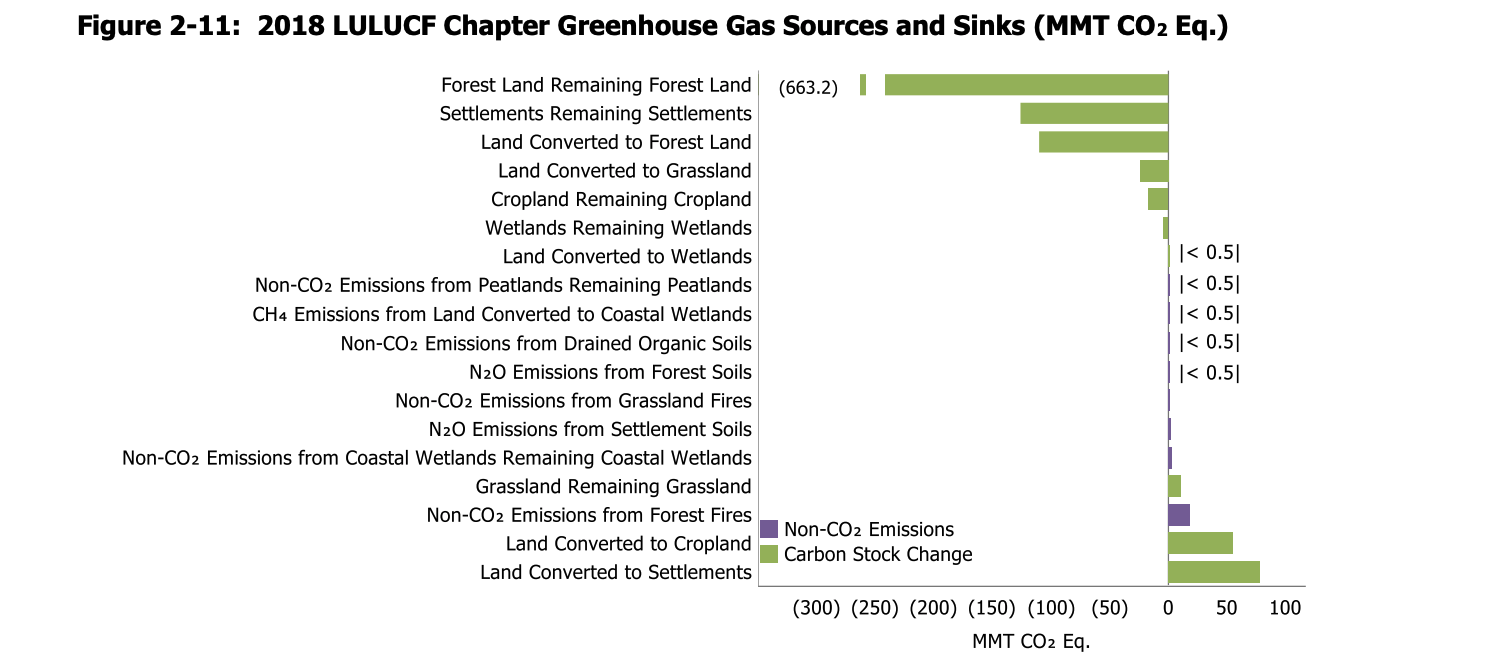

The chart below from a 2020 EPA report shows greenhouse gas balances resulting from “Land Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry (LULUCF)” and illustrates that simply allowing U.S. forests to remain intact (see top line) preserves a huge carbon sink (represented by green block to the left side of the vertical line, as opposed to net carbon additions on the right side):

But while forests are a big help in reducing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, they’re trending in the wrong direction. Between 1990 and 2018, the net carbon dioxide equivalent sequestered by U.S. forests went from 843.3 million metric tons to 733.8 million metric tons—approximately an 8.2 percent decrease.

Another distressing note: Deforestation has ramped up in the last few decades. Between 2000 and 2017, close to 1 billion acres of forest worldwide were disturbed by human activities, droughts and fires. Allowing that pattern to continue and failing to protect key forest land as forest land will severely hamper our ability to keep greenhouse gases in check.

Tongass National Forest, Alaska

Colin Arisman

We know that the age of a forest’s trees is an important factor in how good it is at absorbing carbon pollution. But tree size matters, too; a 2018 study found that forests are unable to store large amounts of carbon without a population of large trees. The authors looked at 48 big forest plots around the world and found that the largest 1% of trees comprise 50% of live forest biomass. Since tree size is closely correlated with carbon capacity, that means the biggest, oldest trees are doing more than their fair share of carbon pollution absorption.