2 tragic moments in Black history that are now commemorated on public lands

USDA Tom Vilsack, US Policy Council Director Susan Rice and Congressman Bennie Thompson, MS CD2, are led on a tour of the Emmett Till Historic Intrepid Center ETHIC by Glendora Mayor Johnny B Thomas in Glendora, MS

USDA Media by Lance Cheung

Emmett Till’s murder, Springfield riot stories preserved on public lands.

The history and future of our country can be read like a book across the landscape. When public lands are protected as national monuments, parks, historic sites or recreation areas, it signals that those places matter and stand testament to a story that is worth remembering and retelling.

But not all places worthy of federal protections end up being recognized. The National Park Service and other land management agencies collectively oversee hundreds of sites totaling millions of acres of public lands but less than one quarter of national monuments and national parks tell stories of Black, Brown, Indigenous, people of color, and LGBTQIA+ communities.

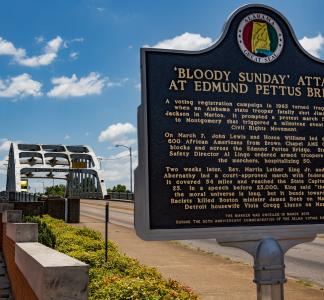

To correct that imbalance, President Biden had the opportunity to uplift and honor stories that have helped shape the very foundation of our country and the civil rights movement. Specifically, two historical events have been commemorated, each of which has been championed by advocates for many years.

The Springfield Race Riot of 1908 (Illinois)

1908 race riot archaeological site in Springfield, Illinois.

June Stricker/Hanson Professional Services Inc./Flickr

In August of 1908, a race war broke out in the capital of Illinois after a white mob was thwarted in its attempts to attack two Black men awaiting trial at the local jail. Once the two men were spirited out of town to a different jail, the white mob turned its anger on the Black community of Springfield, destroying and looting Black-run businesses and homes while thousands of white residents looked on. Ultimately, two Black men were lynched, six people died overall, more than 40 Black families were displaced and hundreds of thousands of dollars in damages were done.

This racist event, among other violent attacks, catalyzed the formation of the civil rights organization the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909.

On August 16 of 2024, the Biden administration designated the Springfield 1908 Race Riot National Monument in the capital of Illinois using the Antiquities Act. This marked the 116th year since the riot, one of the country’s worst examples of mass racial violence.

The murder of Emmett Till (Mississippi)

The Tallahatchie County Courthouse in Sumner, Mississippi, the site of Emmett Till’s murder trial.

Alan Spears/NPCA

In August 1955 in Money, Mississippi, a young Black teenager named Emmett Till was brutally murdered by two white men who accused him of flirting with a white woman. His body was found in a river and brought back to his hometown of Chicago at the request of his mother, who had a public, open-casket funeral so that the world could see the brutality her only son suffered. A month later, an all-white jury found the killers not guilty.

In 2017, the woman who accused Till of flirting with her allegedly recanted her testimony, and in 2022 a grand jury in Mississippi declined to indict her for her role in the crime. Decades after Till’s death, in March 2022, President Biden signed the Emmett Till Antilynching Act into law, finally making lynching a federal hate crime.

Efforts to honor Till have gained momentum in recent years. Advocates and communities across the country called on the National Park Service to designate Till’s funeral site and murder trial site as park sites.

And on July 25th of 2023, the Biden administration designated the Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley National Monument, spanning three sites in Mississippi and Illinois. The sites include the Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ in Chicago, where Till’s funeral was held in an open casket ceremony; Graball Landing in Mississippi, where locals believe that Till’s body was pulled from the Tallahatchie River; and the Tallahatchie County Second District Courthouse in Mississippi, where Roy Bryant and his half-brother J.W. Milam, the two men who kidnapped and killed Till, were acquitted.

These stories are painful but remain relevant. Commemorating the places where they happened allows those stories to never be forgotten.