How a Black family shepherded and protected a Florida national park for generations

Boca Chita lighthouse at Biscayne National Park.

El Gringo, Flickr

Jones family became synonymous with Biscayne National Park, helped defend it from development

Author: Gracie Heim

Biscayne National Park in Florida is part of the world’s third-largest coral reef, containing diverse plant and animal life and traces of nearly 10,000 years’ worth of human history. But it’s possible the area would now be dominated by an oil refinery and other development if it weren’t for the amazing Jones family, whose history in the area lasted close to a century.

Biscayne's human history begins over 10,000 years ago with the migration of Paleo-Indians to the area. Although evidence of their civilization is believed to be at the bottom of Biscayne Bay, archeologists have found evidence of the Tequesta, who lived off the sea nearly 2,500 years ago. The Tequesta were succeeded by the Seminole and Miccosukee, before colonialist expansion and violence forced many Native peoples from the area.

The history of the national park that now occupies that land and water begins with Israel Lafayette “Parson” Jones, born in 1858 in Raleigh, North Carolina. Though there are many gaps in record-keeping from the era, it is very likely Israel or his parents were born into slavery, making the achievements to come even more improbable.

As a young man, Israel’s search for steady work brought him down the East Coast until he settled in Biscayne Key in 1892. Here, he became a foreman on a pineapple farm and developed skills in growing lime and pineapple trees, which would set him up for some sweet—well, sour and tart—success.

The Jones family builds a fruit-growing empire

In 1895, Israel married Mozelle Albury, and their first son, King Arthur Lafayette Jones, was born in 1897. Almost a year and a half later, Sir Lancelot Garfield Jones was born. They are believed to be the first Black Americans born on Key Biscayne.

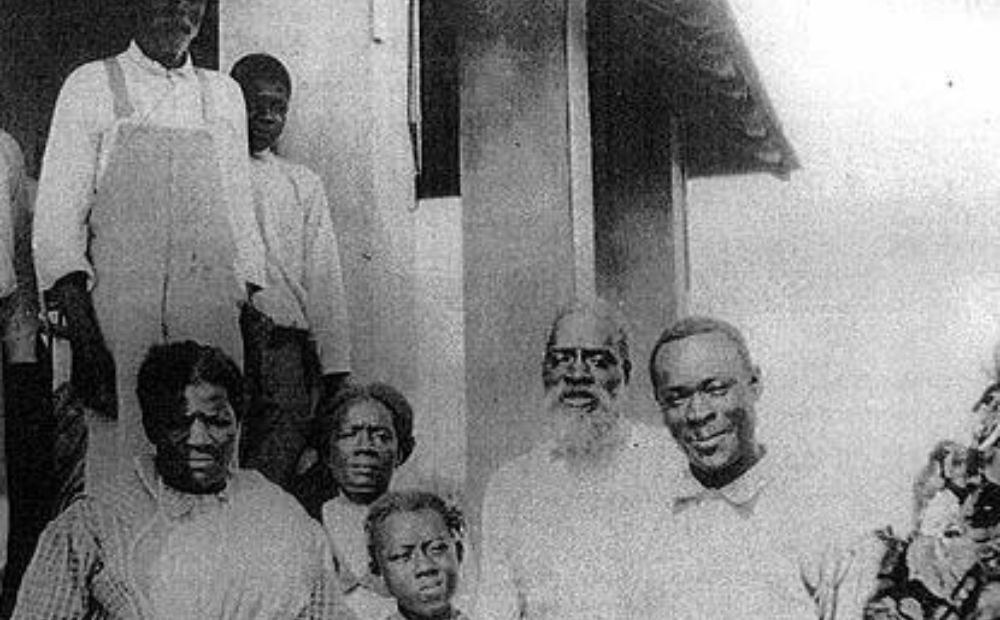

The Jones family poses on the porch of their Porgy Key home.

NPS

Using earnings from his work as a caretaker and foreman, Israel purchased Porgy Key for $300 (the equivalent to about $10,800 today) and became the first Black landowner in the Keys. This achievement was particularly remarkable for the time, as racial segregation and violence constrained the efforts of Black families working to improve their quality of life.

Biscayne’s uninhabited coastal areas continued to attract free Black communities after slavery. “Because it was so untamed and difficult to survive on, it was accessible to the poorest of folks,” according to Joshua Marano, a maritime archeologist with the National Park Service.

Beginning a little before the turn of the century, the Jones family put in years’ worth of tedious work clearing the land by hand. Israel and his sons cut through acres of gumbo-limbo, palmetto, mahogany trees and thorny vines to make way for crops of pineapples, tomatoes and limes that he knew would thrive in the tropical climate. Ignoring traditional planting methods, Israel bunched limes close together to replicate the way they grew in the wild. This compact placement encouraged the plants to compete for space and grow abundantly.

The family soon turned a profit, and eventually the Jones farm became one of the largest producers of pineapples and limes on the East Coast.

Battle between development interests and conservation

In the 1960s, investors launched an effort to develop the Keys, unveiling plans for an oil refinery, petrochemical plants and industrial seaport. Sir Lancelor and Arthur, at the time the second biggest property-owners in the region, knew such development would cause major damage to Biscayne’s aquatic wildlife and historical artifacts--unless they stepped in.

Lancelot turned down offers from refinery developers to buy Porgy Key, and a movement was born to designate the land as a national park and stop the threat of development. Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall eventually came out in favor of protecting the area. In 1968, Congress made Biscayne a national monument, saving 173,000 acres of the bay, coral reefs and islands.

But the threat wasn’t over. In the late 1970s, investors and developers were once again circling. Rather than hand over his family’s land to them, Sir Lancelot sold nearly 277 acres to the National Park Service, enabling the national monument to be transformed into a national park in 1980.

Legacy of the Jones family endures

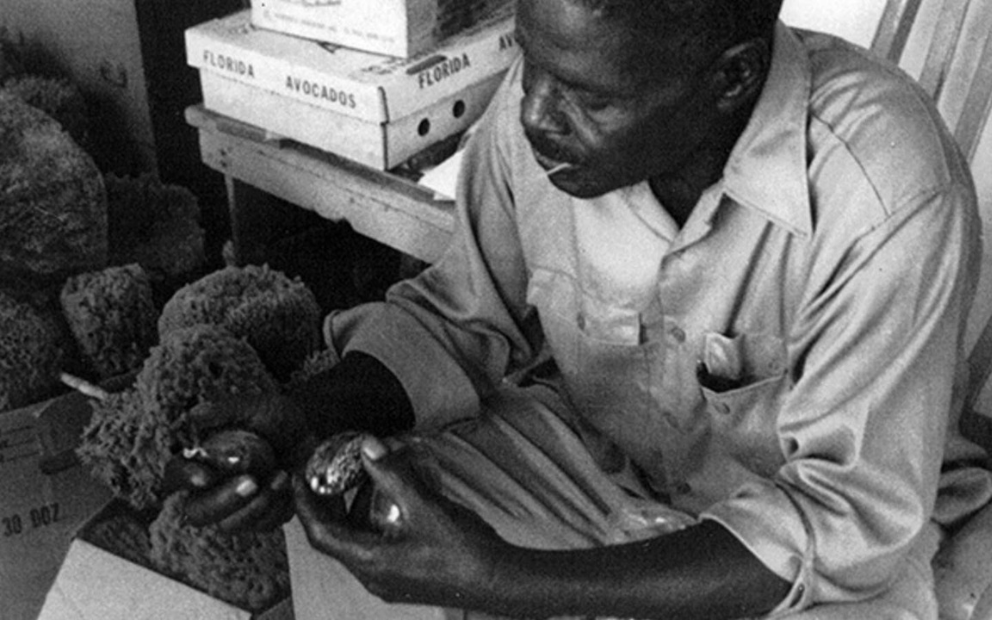

Sir Lancelot continued living in the Jones family home within the park, volunteering for the National Park Service’s environmental education program and talking to schoolchildren about the park’s wildlife. He died on December 22, 1997, at the age of 99.

Today, the rich Black history of Biscayne National Park is remembered through organizations such as Youth Diving With a Purpose, which is dedicated to the conservation and protection of heritage resources found underwater. The organization provides education, training, certification and field experiences, with a particular focus on African slave-trade shipwrecks and the maritime history and culture of African Americans.

Traditional conservation narratives are full of stories about white men, meaning that the contributions of people of color and others can sometimes be forgotten. Part of approaching conservation with a more holistic view means acknowledging and reflecting on those untold stories of public lands--whether about the Indigenous peoples who stewarded these places since time immemorial, or people like the Jones family, who fought to protect Key Biscayne for generations.

If you would like to learn more about the untold stories of our public lands, check out The Wilderness Society’s Public Lands Curriculum, which reflects our broader effort to be more inclusive and equitable in our advocacy for the protection of public lands.

Sir Lancelot Jones with his sea sponges.

NPS